Фармацевтическая промышленность

_(6982162417).jpg/440px-Inspecting_a_Drug_Manufacturer_(FDA034)_(6982162417).jpg)

Фармацевтическая промышленность — это медицинская отрасль, которая занимается открытием, разработкой, производством и продажей фармацевтических товаров , таких как лекарства и медицинские приборы . Затем лекарства вводятся пациентам (или вводятся ими самостоятельно ) для лечения или профилактики заболеваний , а также для облегчения симптомов заболеваний или травм . [1] [2]

Фармацевтические компании могут заниматься дженериками , фирменными препаратами или и тем, и другим в разных контекстах. Дженерики не имеют отношения к интеллектуальной собственности , тогда как фирменные материалы защищены химическими патентами . Различные подразделения отрасли включают в себя различные области, такие как производство биопрепаратов или полный синтез . Отрасль подчиняется различным законам и правилам , которые регулируют патентование , тестирование эффективности, оценку безопасности и маркетинг этих препаратов. В 2020 году мировой фармацевтический рынок произвел лечение на общую сумму 1 228,45 млрд долларов США. В 2021 году сектор продемонстрировал совокупный годовой темп роста (CAGR) в размере 1,8%, включая последствия пандемии COVID-19 . [3]

В историческом плане фармацевтическая промышленность как интеллектуальная концепция возникла в середине-конце 1800-х годов в национальных государствах с развитой экономикой , таких как Германия , Швейцария и США . Некоторые предприятия, занимающиеся синтетической органической химией , например, несколько фирм, производящих красители, полученные из каменноугольной смолы в больших масштабах, искали новые применения для своих искусственных материалов с точки зрения здоровья человека . Эта тенденция увеличения капиталовложений произошла одновременно с научным изучением патологии как области, значительно продвинувшейся вперед, и различные предприятия установили отношения сотрудничества с академическими лабораториями, оценивающими человеческие травмы и заболевания. Примерами промышленных компаний с фармацевтической направленностью, которые сохранились до наших дней после столь отдаленного начала, являются Bayer (базирующаяся в Германии) и Pfizer (базирующаяся в США). [4]

История

Середина 1800-х – 1945

Современная эра фармацевтической промышленности началась с местных аптекарей , которые расширили свою традиционную роль по распространению растительных препаратов, таких как морфин и хинин, до оптового производства в середине 1800-х годов. Преднамеренное открытие лекарств из растений началось с извлечения морфина — анальгетика и снотворного — из опиума немецким помощником аптекаря Фридрихом Сертюрнером где-то между 1803 и 1805 годами. Позже Сертюрнер назвал это соединение в честь греческого бога сновидений Морфея . Многонациональные корпорации, включая Merck , Hoffman-La Roche , Burroughs-Wellcome (теперь часть GSK ), Abbott Laboratories , Eli Lilly и Upjohn (теперь часть Pfizer ), начинали как местные аптекарские магазины в середине 1800-х годов. К концу 1880-х годов немецкие производители красителей усовершенствовали очистку отдельных органических соединений из смолы и других минеральных источников, а также разработали элементарные методы органического химического синтеза . [4] Развитие методов синтетической химии позволило ученым систематически изменять структуру химических веществ, а развитие зарождающейся науки фармакологии расширило их возможности по оценке биологических эффектов этих структурных изменений. [ необходима ссылка ]

Адреналин, норадреналин и амфетамин

К 1890-м годам было обнаружено глубокое воздействие экстрактов надпочечников на многие различные типы тканей, что положило начало поиску как механизма химической сигнализации, так и попыткам использовать эти наблюдения для разработки новых лекарств. Повышение артериального давления и сосудосуживающее действие экстрактов надпочечников представляли особый интерес для хирургов как кровоостанавливающие средства и как средство лечения шока, и ряд компаний разработали продукты на основе экстрактов надпочечников, содержащих различную чистоту активного вещества. В 1897 году Джон Абель из Университета Джонса Хопкинса идентифицировал активное начало как адреналин , который он выделил в неочищенном состоянии в виде сульфатной соли. Промышленный химик Дзёкичи Такамине позже разработал метод получения адреналина в чистом виде и лицензировал технологию компании Parke-Davis . Parke-Davis продавала адреналин под торговым названием Адреналин . Инъекционный адреналин оказался особенно эффективным для лечения острых приступов астмы , а ингаляционная версия продавалась в Соединенных Штатах до 2011 года ( Primatene Mist ). [5] [6] К 1929 году адреналин был разработан в виде ингалятора для использования при лечении заложенности носа.

Несмотря на высокую эффективность, необходимость инъекций ограничивала использование адреналина [ необходимо разъяснение ], и были найдены перорально активные производные. Структурно похожее соединение, эфедрин , было идентифицировано японскими химиками на заводе Ma Huang и выпущено на рынок Eli Lilly в качестве перорального лечения астмы. После работы Генри Дейла и Джорджа Баргера в Burroughs-Wellcome , академический химик Гордон Аллес синтезировал амфетамин и испытал его на пациентах с астмой в 1929 году. Препарат, как оказалось, имел лишь скромные противоастматические эффекты, но вызывал ощущения возбуждения и сердцебиения. Амфетамин был разработан Смитом, Кляйном и Френчем как назальное сосудосуживающее средство под торговым названием бензедриновый ингалятор. В конечном итоге амфетамин был разработан для лечения нарколепсии , постэнцефалитического паркинсонизма и повышения настроения при депрессии и других психиатрических показаниях. В 1937 году он получил одобрение Американской медицинской ассоциации как новое и неофициальное средство для этих целей [7] и оставался широко распространенным средством лечения депрессии до разработки трициклических антидепрессантов в 1960-х годах [6] .

Открытие и разработка барбитуратов

В 1903 году Герман Эмиль Фишер и Йозеф фон Меринг раскрыли свое открытие, что диэтилбарбитуровая кислота, образующаяся в результате реакции диэтилмалоновой кислоты, оксихлорида фосфора и мочевины, вызывает сон у собак. Открытие было запатентовано и лицензировано Bayer Pharmaceuticals , которая продавала соединение под торговым названием Veronal как снотворное, начиная с 1904 года. Систематические исследования влияния структурных изменений на силу и продолжительность действия привели к открытию фенобарбитала в Bayer в 1911 году и открытию его мощной противоэпилептической активности в 1912 году. Фенобарбитал был одним из наиболее широко используемых препаратов для лечения эпилепсии в 1970-х годах и по состоянию на 2014 год остается в списке основных лекарственных средств Всемирной организации здравоохранения. [8] [9] В 1950-х и 1960-х годах возросла осведомленность о вызывающих привыкание свойствах и потенциале злоупотребления барбитуратами и амфетаминами, что привело к ужесточению ограничений на их использование и усилению государственного надзора за врачами, выписывающими рецепты. Сегодня амфетамин в значительной степени ограничен для использования при лечении синдрома дефицита внимания , а фенобарбитал — при лечении эпилепсии . [10] [11]

В 1958 году Лео Штернбах открыл первый бензодиазепин , хлордиазепоксид (Либриум). Были разработаны и используются десятки других бензодиазепинов, некоторые из наиболее популярных препаратов - диазепам (Валиум), алпразолам (Ксанакс), клоназепам (Клонопин) и лоразепам (Ативан). Благодаря своей гораздо более высокой безопасности и терапевтическим свойствам бензодиазепины в значительной степени заменили использование барбитуратов в медицине, за исключением некоторых особых случаев. Когда позже было обнаружено, что бензодиазепины, как и барбитураты, значительно теряют свою эффективность и могут иметь серьезные побочные эффекты при длительном приеме, Хизер Эштон исследовала зависимость от бензодиазепинов и разработала протокол прекращения их использования. [ необходима цитата ]

инсулин

Серия экспериментов, проведенных с конца 1800-х до начала 1900-х годов, показала, что диабет вызван отсутствием вещества, обычно вырабатываемого поджелудочной железой. В 1869 году Оскар Минковский и Йозеф фон Меринг обнаружили, что диабет можно вызвать у собак путем хирургического удаления поджелудочной железы. В 1921 году канадский профессор Фредерик Бантинг и его студент Чарльз Бест повторили это исследование и обнаружили, что инъекции экстракта поджелудочной железы устраняют симптомы, вызванные удалением поджелудочной железы. Вскоре было продемонстрировано, что экстракт действует на людей, но развитие инсулинотерапии как обычной медицинской процедуры было отложено из-за трудностей с производством материала в достаточном количестве и с воспроизводимой чистотой. Исследователи обратились за помощью к промышленным партнерам в Eli Lilly and Co., основываясь на опыте компании в области крупномасштабной очистки биологических материалов. Химик Джордж Б. Уолден из Eli Lilly and Company обнаружил, что тщательная регулировка pH экстракта позволяет производить относительно чистый класс инсулина. Под давлением Университета Торонто и потенциального патентного оспаривания со стороны академических ученых, которые независимо разработали аналогичный метод очистки, было достигнуто соглашение о неисключительном производстве инсулина несколькими компаниями. До открытия и широкого распространения инсулиновой терапии продолжительность жизни диабетиков составляла всего несколько месяцев. [12]

Ранние противоинфекционные исследования: сальварсан, пронтозил, пенициллин и вакцины

Разработка лекарств для лечения инфекционных заболеваний была основным направлением ранних исследований и разработок; в 1900 году пневмония, туберкулез и диарея были тремя основными причинами смерти в Соединенных Штатах, а смертность в первый год жизни превышала 10%. [13] [14] [ проверка не удалась ]

В 1911 году Пауль Эрлих и химик Альфред Бертхайм из Института экспериментальной терапии в Берлине разработали арсфенамин , первый синтетический противоинфекционный препарат. Препарату было дано коммерческое название сальварсан. [15] Эрлих, отметив как общую токсичность мышьяка , так и избирательное поглощение некоторых красителей бактериями, выдвинул гипотезу, что краситель, содержащий мышьяк, с аналогичными свойствами избирательного поглощения может быть использован для лечения бактериальных инфекций. Арсфенамин был получен в рамках кампании по синтезу серии таких соединений и проявил частично избирательную токсичность. Арсфенамин оказался первым эффективным средством лечения сифилиса , заболевания, которое до тех пор было неизлечимым и неумолимо приводило к тяжелым изъязвлениям кожи, неврологическим повреждениям и смерти. [16]

Подход Эрлиха к систематическому изменению химической структуры синтетических соединений и измерению эффектов этих изменений на биологическую активность широко использовался промышленными учеными, включая ученых Bayer Йозефа Кларера, Фрица Митча и Герхарда Домагка . Эта работа, также основанная на тестировании соединений, доступных в немецкой красильной промышленности, привела к разработке Пронтозила , первого представителя класса сульфонамидных антибиотиков . По сравнению с арсфенамином, сульфонамиды имели более широкий спектр действия и были гораздо менее токсичными, что делало их полезными при инфекциях, вызванных такими патогенами, как стрептококки . [17] В 1939 году Домагк получил Нобелевскую премию по медицине за это открытие. [18] [19] Тем не менее, резкое снижение смертности от инфекционных заболеваний, произошедшее до Второй мировой войны, было в первую очередь результатом улучшения мер общественного здравоохранения, таких как чистая вода и менее перенаселенное жилье, а влияние противоинфекционных препаратов и вакцин было значительным, в основном, после Второй мировой войны. [20] [21]

В 1928 году Александр Флеминг открыл антибактериальные эффекты пенициллина , но его использование для лечения человеческих болезней ожидало разработки методов его крупномасштабного производства и очистки. Они были разработаны консорциумом фармацевтических компаний под руководством правительства США и Великобритании во время мировой войны. [22]

В течение этого периода наблюдался ранний прогресс в разработке вакцин, в первую очередь в форме академических и финансируемых правительством фундаментальных исследований, направленных на выявление патогенов, ответственных за распространенные инфекционные заболевания. В 1885 году Луи Пастер и Пьер Поль Эмиль Ру создали первую вакцину против бешенства . Первые вакцины против дифтерии были произведены в 1914 году из смеси дифтерийного токсина и антитоксина (полученного из сыворотки инокулированного животного), но безопасность прививки была незначительной, и она не получила широкого распространения. В 1921 году в Соединенных Штатах было зарегистрировано 206 000 случаев дифтерии, что привело к 15 520 смертельным исходам. В 1923 году параллельные усилия Гастона Рамона из Института Пастера и Александра Гленни из Исследовательских лабораторий Уэллкома (позже часть GlaxoSmithKline ) привели к открытию того, что более безопасную вакцину можно получить, обработав дифтерийный токсин формальдегидом . [ 23] В 1944 году Морис Хиллеман из Squibb Pharmaceuticals разработал первую вакцину против японского энцефалита . [24] Позднее Хиллеман перешел в Merck , где сыграл ключевую роль в разработке вакцин против кори , эпидемического паротита , ветряной оспы , краснухи , гепатита А , гепатита В и менингита .

Небезопасные лекарства и раннее регулирование отрасли

До 20 века лекарства, как правило, производились мелкими производителями с небольшим регулирующим контролем над производством или заявлениями о безопасности и эффективности. В той степени, в которой такие законы существовали, исполнение было слабым. В Соединенных Штатах усиление регулирования вакцин и других биологических препаратов было вызвано вспышками столбняка и смертями, вызванными распространением зараженной вакцины против оспы и дифтерийного антитоксина. [25] Закон о контроле над биологическими препаратами 1902 года требовал, чтобы федеральное правительство выдавало предварительное одобрение для каждого биологического препарата, а также для процесса и предприятия, производящего такие препараты. За этим в 1906 году последовал Закон о чистых пищевых продуктах и лекарствах , который запрещал межгосударственное распространение фальсифицированных или неправильно маркированных продуктов питания и лекарств. Лекарство считалось неправильно маркированным, если оно содержало алкоголь, морфин, опиум, кокаин или любой из нескольких других потенциально опасных или вызывающих привыкание препаратов, и если на его этикетке не было указано количество или пропорция таких препаратов. Попытки правительства использовать закон для преследования производителей за необоснованные заявления об эффективности были подорваны постановлением Верховного суда, ограничивающим полномочия федерального правительства по обеспечению соблюдения закона случаями неправильной спецификации ингредиентов препарата. [26]

В 1937 году более 100 человек умерли после приема « Эликсира сульфаниламида », произведенного компанией SE Massengill Company из Теннесси. Продукт был изготовлен на основе диэтиленгликоля , высокотоксичного растворителя, который в настоящее время широко используется в качестве антифриза. [27] Согласно законам, существовавшим в то время, судебное преследование производителя было возможно только на основании того, что продукт был назван «эликсиром», что подразумевало раствор в этаноле. В ответ на этот эпизод Конгресс США принял Федеральный закон о пищевых продуктах, лекарственных средствах и косметике 1938 года , который впервые потребовал предпродажной демонстрации безопасности перед продажей препарата и прямо запретил ложные терапевтические заявления. [28]

1945–1970

Дальнейшие достижения в исследованиях противоинфекционных препаратов

После Второй мировой войны произошел взрыв в открытии новых классов антибактериальных препаратов [29], включая цефалоспорины (разработанные Eli Lilly на основе основополагающих работ Джузеппе Бротцу и Эдварда Абрахама ), [30] [31] стрептомицин (открытый в ходе финансируемой Merck исследовательской программы в лаборатории Селмана Ваксмана [32] ), тетрациклины [33] (открытые в Lederle Laboratories, ныне являющейся частью Pfizer ), эритромицин (открытый в Eli Lilly and Co.) [34] и их распространение на все более широкий спектр бактериальных патогенов. Стрептомицин, открытый в ходе финансируемой Merck исследовательской программы в лаборатории Селмана Ваксмана в Ратгерсе в 1943 году, стал первым эффективным средством лечения туберкулеза. На момент его открытия санатории для изоляции больных туберкулезом были повсеместным явлением в городах развитых стран, и 50% из них умирали в течение 5 лет после поступления. [32] [35]

В отчете Федеральной торговой комиссии, выпущенном в 1958 году, была предпринята попытка количественно оценить влияние разработки антибиотиков на американское общественное здравоохранение. В отчете было установлено, что за период с 1946 по 1955 год наблюдалось 42%-ное снижение заболеваемости болезнями, при которых антибиотики были эффективны, и только 20%-ное снижение тех, при которых антибиотики не были эффективны. В отчете сделан вывод, что «похоже, что использование антибиотиков, ранняя диагностика и другие факторы ограничили распространение эпидемии и, таким образом, количество этих заболеваний, которые произошли». Исследование далее изучило показатели смертности от восьми распространенных заболеваний, при которых антибиотики предлагали эффективную терапию (сифилис, туберкулез, дизентерия, скарлатина, коклюш, менингококковые инфекции и пневмония), и обнаружило 56%-ное снижение за тот же период. [36] Среди них следует отметить 75%-ное снижение смертности от туберкулеза. [37]

В 1940–1955 годах темпы снижения смертности в США ускорились с 2% в год до 8% в год, а затем вернулись к историческому показателю в 2% в год. Резкое снижение в первые послевоенные годы объясняется быстрым развитием новых методов лечения и вакцин от инфекционных заболеваний, которое произошло в эти годы. [39] [21] Разработка вакцин продолжала ускоряться, и наиболее заметным достижением этого периода стала разработка Джонасом Солком в 1954 году вакцины против полиомиелита при финансировании некоммерческого Национального фонда детского паралича . Процесс вакцинации никогда не был запатентован, а вместо этого был передан фармацевтическим компаниям для производства в качестве недорогого дженерика . В 1960 году Морис Хиллеман из Merck Sharp & Dohme идентифицировал вирус SV40 , который, как позже было показано, вызывает опухоли у многих видов млекопитающих. Позже было установлено, что SV40 присутствовал в качестве загрязнителя в партиях вакцины от полиомиелита, которые были введены 90% детей в Соединенных Штатах. [40] [41] Загрязнение, по-видимому, возникло как в исходном запасе клеток, так и в тканях обезьян, используемых для производства. В 2004 году Национальный институт рака объявил, что он пришел к выводу, что SV40 не связан с раком у людей. [42]

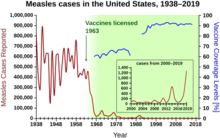

Другие известные новые вакцины того периода включают вакцины от кори (1962, Джон Франклин Эндерс из Детского медицинского центра в Бостоне, позднее усовершенствованные Морисом Хиллеманом из Merck), краснухи (1969, Хиллеманом, Merck) и эпидемического паротита (1967, Хиллеман, Merck) [43] Заболеваемость краснухой, синдромом врожденной краснухи, корью и паротитом в Соединенных Штатах снизилась более чем на 95% сразу после широкомасштабной вакцинации. [44] Первые 20 лет лицензированной вакцинации от кори в США предотвратили, по оценкам, 52 миллиона случаев заболевания, 17 400 случаев умственной отсталости и 5200 смертей. [45]

Разработка и маркетинг антигипертензивных препаратов

Гипертония является фактором риска атеросклероза, [46] сердечной недостаточности , [47] ишемической болезни сердца , [48] [49] инсульта , [50] заболеваний почек , [51] [52] и заболеваний периферических артерий , [53] [54] и является наиболее важным фактором риска сердечно -сосудистой заболеваемости и смертности в промышленно развитых странах . [55] До 1940 года примерно 23% всех смертей среди людей старше 50 лет были связаны с гипертонией. Тяжелые случаи гипертонии лечились хирургическим путем. [56]

Ранние разработки в области лечения гипертонии включали блокаторы симпатической нервной системы на основе четвертичных аммониевых ионов, но эти соединения никогда не использовались широко из-за их серьезных побочных эффектов, поскольку долгосрочные последствия для здоровья высокого кровяного давления еще не были установлены, а также потому, что их приходилось вводить путем инъекций.

В 1952 году исследователи из Ciba открыли первый перорально доступный вазодилататор, гидралазин . [57] Основным недостатком монотерапии гидралазином было то, что он терял свою эффективность с течением времени ( тахифилаксия ). В середине 1950-х годов Карл Х. Бейер, Джеймс М. Спраг, Джон Э. Баер и Фредерик К. Новелло из Merck and Co. открыли и разработали хлоротиазид , который остается наиболее широко используемым антигипертензивным препаратом сегодня. [58] Это развитие было связано со значительным снижением уровня смертности среди людей с гипертонией. [59] Изобретатели были отмечены премией Ласкера в области общественного здравоохранения в 1975 году за «спасение неисчислимых тысяч жизней и облегчение страданий миллионов жертв гипертонии». [60]

Обзор Cochrane 2009 года пришел к выводу, что тиазидные антигипертензивные препараты снижают риск смерти ( RR 0,89), инсульта (RR 0,63), ишемической болезни сердца (RR 0,84) и сердечно-сосудистых событий (RR 0,70) у людей с высоким кровяным давлением. [61] В последующие годы были разработаны и нашли широкое применение в комбинированной терапии другие классы антигипертензивных препаратов, включая петлевые диуретики (Lasix/ furosemide , Hoechst Pharmaceuticals , 1963), [62] бета-блокаторы ( ICI Pharmaceuticals , 1964) [63] ингибиторы АПФ и блокаторы рецепторов ангиотензина . Ингибиторы АПФ снижают риск впервые возникшего заболевания почек [RR 0,71] и смерти [RR 0,84] у пациентов с диабетом, независимо от того, страдают ли они гипертонией. [64]

Оральные контрацептивы

До Второй мировой войны контроль рождаемости был запрещен во многих странах, а в Соединенных Штатах даже обсуждение методов контрацепции иногда приводило к судебному преследованию по законам Комстока . Таким образом, история разработки оральных контрацептивов тесно связана с движением за контроль рождаемости и усилиями активистов Маргарет Сэнгер , Мэри Деннетт и Эммы Голдман . На основе фундаментальных исследований, проведенных Грегори Пинкуса , и синтетических методов получения прогестерона, разработанных Карлом Джерасси в Syntex и Фрэнком Колтоном в GD Searle & Co. , первый оральный контрацептив, Эновид , был разработан GD Searle & Co. и одобрен FDA в 1960 году. Первоначальная формула включала в себя значительно чрезмерные дозы гормонов и вызывала серьезные побочные эффекты. Тем не менее, к 1962 году 1,2 миллиона американских женщин принимали таблетки, а к 1965 году их число возросло до 6,5 миллионов. [65] [66] [67] [68] Доступность удобной формы временной контрацепции привела к резким изменениям в общественных нравах, включая расширение спектра вариантов образа жизни, доступных женщинам, снижение зависимости женщин от мужчин в вопросах контрацепции, поощрение отсрочки вступления в брак и увеличение количества добрачных сожительств. [69]

Талидомид и поправки Кефовера-Харриса

В США призыв к пересмотру Закона о FD&C возник в результате слушаний в Конгрессе под руководством сенатора Эстеса Кефовера из Теннесси в 1959 году. Слушания охватывали широкий спектр политических вопросов, включая злоупотребления в рекламе, сомнительную эффективность лекарств и необходимость более строгого регулирования отрасли. В то время как импульс для нового законодательства временно ослабел из-за продолжительных дебатов, возникла новая трагедия, которая подчеркнула необходимость более всеобъемлющего регулирования и стала движущей силой для принятия новых законов.

12 сентября 1960 года американский лицензиат, компания William S. Merrell Company из Цинциннати, подала новую заявку на регистрацию препарата Кевадон ( талидомид ), седативного средства , которое продавалось в Европе с 1956 года. Медицинский сотрудник FDA, отвечающий за рассмотрение соединения, Фрэнсис Келси , считал, что данные, подтверждающие безопасность талидомида, были неполными. Фирма продолжала оказывать давление на Келси и FDA, чтобы они одобрили заявку до ноября 1961 года, когда препарат был снят с немецкого рынка из-за его связи с серьезными врожденными аномалиями. Несколько тысяч новорожденных в Европе и других странах пострадали от тератогенного действия талидомида. Без одобрения FDA фирма распространила Кевадон среди более чем 1000 врачей под видом исследовательского использования. В этом «исследовании» талидомид получили более 20 000 американцев, в том числе 624 беременные пациентки, и около 17 известных новорожденных пострадали от последствий приема препарата. [ необходима цитата ]

Трагедия с талидомидом воскресила законопроект Кефовера об усилении регулирования лекарственных средств, который застрял в Конгрессе, и поправка Кефовера-Харриса стала законом 10 октября 1962 года. С этого момента производители должны были доказать FDA, что их препараты эффективны и безопасны, прежде чем они могли выйти на рынок США. FDA получила полномочия регулировать рекламу рецептурных препаратов и устанавливать надлежащую производственную практику . Закон требовал, чтобы все препараты, представленные в период с 1938 по 1962 год, были эффективными. Совместное исследование Управления по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами США и Национальной академии наук показало, что почти 40 процентов этих продуктов были неэффективны. Аналогичное всестороннее исследование безрецептурных продуктов началось десять лет спустя. [70]

1970–1990-е годы

Статины

В 1971 году Акира Эндо , японский биохимик, работавший в фармацевтической компании Sankyo, идентифицировал мевастатин (ML-236B), молекулу, вырабатываемую грибком Penicillium citrinum , как ингибитор ГМГ-КоА-редуктазы, важнейшего фермента, используемого организмом для производства холестерина. Испытания на животных показали очень хорошие ингибирующие эффекты, как и в клинических испытаниях , однако долгосрочное исследование на собаках обнаружило токсические эффекты при более высоких дозах, и в результате мевастатин считался слишком токсичным для использования человеком. Мевастатин никогда не продавался из-за его побочных эффектов в виде опухолей, ухудшения состояния мышц, а иногда и смерти у лабораторных собак.

П. Рой Вагелос , главный научный сотрудник и позднее генеральный директор Merck & Co , заинтересовался и совершил несколько поездок в Японию, начиная с 1975 года. К 1978 году Merck выделил ловастатин (мевинолин, MK803) из грибка Aspergillus terreus , впервые выпущенный на рынок в 1987 году под названием Mevacor. [71] [72] [73]

В апреле 1994 года были объявлены результаты спонсируемого Merck исследования Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study . Исследователи протестировали симвастатин , позже проданный Merck как Zocor, на 4444 пациентах с высоким уровнем холестерина и сердечными заболеваниями. Через пять лет исследование пришло к выводу, что у пациентов наблюдалось снижение уровня холестерина на 35%, а их шансы умереть от сердечного приступа снизились на 42%. [74] В 1995 году Zocor и Mevacor принесли Merck более 1 миллиарда долларов США. Эндо был награжден премией Японии 2006 года и премией Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award в 2008 году. За его «новаторское исследование нового класса молекул» для «снижения уровня холестерина» [ фрагмент предложения ] [75] [76]

21 век

В течение нескольких десятилетий биопрепараты приобретали все большую значимость по сравнению с лечением малыми молекулами. Биотехнологический подсектор, ветеринария и китайский фармацевтический сектор также существенно выросли. С организационной точки зрения крупные международные фармацевтические корпорации испытали существенное снижение своей доли стоимости. Кроме того, основной сектор дженериков (заменители непатентованных брендов) был обесценен из-за конкуренции. [77]

По оценкам Торрея, к февралю 2021 года рыночная стоимость фармацевтической промышленности составит 7,03 трлн долларов США, из которых 6,1 трлн долларов США — это стоимость публичных компаний. На долю малых молекул пришлось 58,2% доли оценки по сравнению с 84,6% в 2003 году. Биологические препараты выросли с 14,5% до 30,5%. Доля оценки китайской фармацевтики выросла с 2003 по 2021 год с 1% до 12%, обогнав Швейцарию, которая сейчас занимает 3-е место с 7,7%. У Соединенных Штатов по-прежнему самая дорогая фармацевтическая промышленность с 40% глобальной оценки. [78] 2023 год стал годом увольнений по меньшей мере 10 000 человек в 129 публичных биотехнологических компаниях по всему миру, хотя большинство из них были небольшими; это было значительное увеличение сокращений по сравнению с 2022 годом, что отчасти было обусловлено ухудшением мировых финансовых условий и сокращением инвестиций со стороны «инвесторов общего профиля». [79] Частные фирмы также столкнулись с существенным сокращением венчурных инвестиций в 2023 году, что продолжило тенденцию к снижению, начатую в 2021 году, что также привело к сокращению первичных публичных размещений акций . [79]

Влияние слияний и поглощений

В статье 2022 года эта идея была кратко сформулирована следующим образом: «В бизнесе разработки лекарств сделки могут быть столь же важны, как и научные прорывы», обычно называемые фармацевтическими слияниями и поглощениями (для слияний и поглощений). [80] В ней подчеркивается, что некоторые из наиболее эффективных средств правовой защиты начала 21-го века стали возможны только благодаря слияниям и поглощениям, в частности, отмечены Кейтруда и Хумира . [80]

Исследования и разработки

Открытие лекарств — это процесс, посредством которого потенциальные лекарства обнаруживаются или разрабатываются. В прошлом большинство лекарств открывались либо путем выделения активного ингредиента из традиционных средств, либо путем счастливого открытия. Современная биотехнология часто фокусируется на понимании метаболических путей, связанных с болезненным состоянием или патогеном , и манипулировании этими путями с помощью молекулярной биологии или биохимии . Большая часть ранних стадий открытия лекарств традиционно проводилась университетами и научно-исследовательскими институтами.

Разработка лекарств относится к действиям, предпринимаемым после того, как соединение идентифицировано как потенциальное лекарство, чтобы установить его пригодность в качестве лекарства. Цели разработки лекарств - определить соответствующую формулу и дозировку , а также установить безопасность . Исследования в этих областях обычно включают комбинацию исследований in vitro , исследований in vivo и клинических испытаний . Стоимость разработки на поздней стадии означает, что ее обычно выполняют более крупные фармацевтические компании. [81] Фармацевтическая и биотехнологическая промышленность тратит более 15% своих чистых продаж на исследования и разработки, что по сравнению с другими отраслями является самой высокой долей. [82]

Часто крупные многонациональные корпорации демонстрируют вертикальную интеграцию , участвуя в широком спектре исследований и разработок лекарственных препаратов, производства и контроля качества, маркетинга, продаж и дистрибуции. Более мелкие организации, с другой стороны, часто фокусируются на конкретном аспекте, таком как открытие кандидатов на лекарственные препараты или разработка формул. Часто соглашения о сотрудничестве между исследовательскими организациями и крупными фармацевтическими компаниями заключаются для изучения потенциала новых лекарственных веществ. В последнее время многонациональные корпорации все чаще полагаются на контрактные исследовательские организации для управления разработкой лекарственных препаратов. [83]

Стоимость инноваций

Открытие и разработка лекарств обходятся очень дорого; из всех соединений, исследованных для использования на людях, только небольшая часть в конечном итоге одобряется в большинстве стран назначенными правительством медицинскими учреждениями или советами, которые должны одобрить новые лекарства, прежде чем они могут быть проданы в этих странах. В 2010 году было одобрено 18 НМЭ (новых молекулярных сущностей) и три биологических препарата FDA, или 21 в общей сложности, что меньше, чем 26 в 2009 году и 24 в 2008 году. С другой стороны, в 2007 году было всего 18 одобрений, а в 2006 году — 22. С 2001 года Центр оценки и исследований лекарств в среднем получал 22,9 одобрений в год. [84] Это одобрение приходит только после крупных инвестиций в доклиническую разработку и клинические испытания , а также приверженности постоянному мониторингу безопасности . Лекарства, которые терпят неудачу на полпути этого процесса, часто влекут за собой большие расходы, не принося при этом никакой прибыли. Если принять во внимание стоимость этих неудачных лекарств, то стоимость разработки успешного нового лекарства ( нового химического вещества , или NCE) оценивается в 1,3 млрд долларов США [85] (не включая расходы на маркетинг ). Однако в 2012 году профессора Лайт и Лексчин сообщили, что уровень одобрения новых лекарств был относительно стабильным и составлял в среднем от 15 до 25 на протяжении десятилетий. [86]

Исследования и инвестиции в отрасль в целом достигли рекордных 65,3 млрд долларов в 2009 году. [87] Хотя стоимость исследований в США в период с 1995 по 2010 год составляла около 34,2 млрд долларов, доходы росли быстрее (за это время доходы выросли на 200,4 млрд долларов). [86]

Исследование консалтинговой фирмы Bain & Company показало, что стоимость открытия, разработки и запуска (включая маркетинговые и другие деловые расходы) нового препарата (вместе с перспективными препаратами, которые не прошли проверку) выросла за пятилетний период почти до 1,7 млрд долларов в 2003 году. [88] По данным Forbes, к 2010 году расходы на разработку составляли от 4 до 11 млрд долларов на препарат. [89]

Некоторые из этих оценок также учитывают альтернативную стоимость инвестирования капитала за много лет до получения доходов (см. Временная стоимость денег ). Из-за очень длительного времени, необходимого для открытия, разработки и одобрения фармацевтических препаратов, эти затраты могут накапливаться до почти половины общих расходов. Прямым следствием в цепочке создания стоимости фармацевтической промышленности является то, что крупные фармацевтические транснациональные корпорации имеют тенденцию все больше передавать на аутсорсинг риски, связанные с фундаментальными исследованиями, что несколько меняет экосистему отрасли, поскольку биотехнологические компании играют все более важную роль, и общие стратегии соответствующим образом пересматриваются. [90] Некоторые одобренные препараты, такие как те, которые основаны на переформулировании существующего активного ингредиента (также называемые расширениями линейки), гораздо менее затратны в разработке.

Одобрение продукта

В Соединенных Штатах новые фармацевтические продукты должны быть одобрены Управлением по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами (FDA) как безопасные и эффективные. Этот процесс обычно включает подачу заявки на исследовательский новый препарат (IND) с достаточными доклиническими данными для поддержки продолжения испытаний на людях. После одобрения IND могут быть проведены три фазы постепенно увеличивающихся клинических испытаний на людях. Фаза I обычно изучает токсичность с использованием здоровых добровольцев. Фаза II может включать фармакокинетику и дозирование у пациентов, а фаза III представляет собой очень большое исследование эффективности в предполагаемой популяции пациентов. После успешного завершения испытаний фазы III в FDA подается заявка на новый препарат . FDA рассматривает данные, и если продукт рассматривается как имеющий положительную оценку пользы и риска, выдается разрешение на продажу продукта в США. [91]

Четвертая фаза пострегистрационного наблюдения также часто требуется из-за того, что даже самые крупные клинические испытания не могут эффективно предсказать распространенность редких побочных эффектов. Пострегистрационный надзор гарантирует, что после выхода на рынок безопасность препарата тщательно контролируется. В некоторых случаях его показания могут быть ограничены определенными группами пациентов, а в других случаях вещество полностью изымается с рынка.

FDA предоставляет информацию об одобренных препаратах на сайте Orange Book. [92]

In the UK, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approves and evaluates drugs for use. Normally an approval in the UK and other European countries comes later than one in the USA. Then it is the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), for England and Wales, who decides if and how the National Health Service (NHS) will allow (in the sense of paying for) their use. The British National Formulary is the core guide for pharmacists and clinicians.

In many non-US western countries, a 'fourth hurdle' of cost effectiveness analysis has developed before new technologies can be provided. This focuses on the 'efficacy price tag' (in terms of, for example, the cost per QALY) of the technologies in question. In England and Wales NICE decides whether and in what circumstances drugs and technologies will be made available by the NHS, whilst similar arrangements exist with the Scottish Medicines Consortium in Scotland, and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in Australia. A product must pass the threshold for cost-effectiveness if it is to be approved. Treatments must represent 'value for money' and a net benefit to society.

Orphan drugs

There are special rules for certain rare diseases ("orphan diseases") in several major drug regulatory territories. For example, diseases involving fewer than 200,000 patients in the United States, or larger populations in certain circumstances are subject to the Orphan Drug Act.[93] Because medical research and development of drugs to treat such diseases is financially disadvantageous, companies that do so are rewarded with tax reductions, fee waivers, and market exclusivity on that drug for a limited time (seven years), regardless of whether the drug is protected by patents.

Global sales

| Company | Pharma revenue ($ million) |

|---|---|

Pfizer  | 100,330 |

Johnson & Johnson  | 94,940 |

Roche  | 66,260 |

Merck & Co  | 59,280 |

Abbvie  | 58,050 |

Novartis  | 50,540 |

Bristol Myers Squibb  | 46,160 |

Sanofi  | 45,220 |

AstraZeneca  / / | 44,350 |

GSK  | 36,150 |

Takeda  | 30,000 |

Eli Lilly and Company  | 28,550 |

Gilead Sciences  | 27,280 |

Bayer  | 26,640 |

Amgen  | 26,320 |

Boehringer Ingelheim  | 25,280 |

Novo Nordisk  | 25,000 |

Moderna  | 19,260 |

Merck KGaA  | 19,160 |

BioNTech  | 18,200 |

In 2011, global spending on prescription drugs topped $954 billion, even as growth slowed somewhat in Europe and North America. The United States accounts for more than a third of the global pharmaceutical market, with $340 billion in annual sales followed by the EU and Japan.[95] Emerging markets such as China, Russia, South Korea and Mexico outpaced that market, growing a huge 81 percent.[96][97]

The top ten best-selling drugs of 2013 totaled $75.6 billion in sales, with the anti-inflammatory drug Humira being the best-selling drug worldwide at $10.7 billion in sales. The second and third best selling were Enbrel and Remicade, respectively.[98] The top three best-selling drugs in the United States in 2013 were Abilify ($6.3 billion,) Nexium ($6 billion) and Humira ($5.4 billion).[99] The best-selling drug ever, Lipitor, averaged $13 billion annually and netted $141 billion total over its lifetime before Pfizer's patent expired in November 2011.

IMS Health publishes an analysis of trends expected in the pharmaceutical industry in 2007, including increasing profits in most sectors despite loss of some patents, and new 'blockbuster' drugs on the horizon.[100]

Patents and generics

Depending on a number of considerations, a company may apply for and be granted a patent for the drug, or the process of producing the drug, granting exclusivity rights typically for about 20 years.[101] However, only after rigorous study and testing, which takes 10 to 15 years on average, will governmental authorities grant permission for the company to market and sell the drug.[102] Patent protection enables the owner of the patent to recover the costs of research and development through high profit margins for the branded drug. When the patent protection for the drug expires, a generic drug is usually developed and sold by a competing company. The development and approval of generics are less expensive, allowing them to be sold at a lower price. Often the owner of the branded drug will introduce a generic version before the patent expires in order to get a head start in the generic market.[103] Restructuring has therefore become routine, driven by the patent expiration of products launched during the industry's "golden era" in the 1990s and companies' failure to develop sufficient new blockbuster products to replace lost revenues.[104]

Prescriptions

In the U.S., the value of prescriptions increased over the period of 1995 to 2005 by 3.4 billion annually, a 61 percent increase. Retail sales of prescription drugs jumped 250 percent from $72 billion to $250 billion, while the average price of prescriptions more than doubled from $30 to $68.[105]

Marketing

Advertising is common in healthcare journals as well as through more mainstream media routes. In some countries, notably the US, they are allowed to advertise directly to the general public. Pharmaceutical companies generally employ salespeople (often called 'drug reps' or, an older term, 'detail men') to market directly and personally to physicians and other healthcare providers. In some countries, notably the US, pharmaceutical companies also employ lobbyists to influence politicians. Marketing of prescription drugs in the US is regulated by the federal Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987. The pharmaceutical marketing plan incorporates the spending plans, channels, and thoughts which will take the drug association, and its items and administrations, forward in the current scene.

To healthcare professionals

The book Bad Pharma also discusses the influence of drug representatives, how ghostwriters are employed by the drug companies to write papers for academics to publish, how independent the academic journals really are, how the drug companies finance doctors' continuing education, and how patients' groups are often funded by industry.[106]

Direct to consumer advertising

Since the 1980s, new methods of marketing prescription drugs to consumers have become important. Direct-to-consumer media advertising was legalised in the FDA Guidance for Industry on Consumer-Directed Broadcast Advertisements.

Controversies

Drug marketing and lobbying

There has been increasing controversy surrounding pharmaceutical marketing and influence. There have been accusations and findings of influence on doctors and other health professionals through drug reps including the constant provision of marketing 'gifts' and biased information to health professionals;[107] highly prevalent advertising in journals and conferences; funding independent healthcare organizations and health promotion campaigns; lobbying physicians and politicians (more than any other industry in the US[108]); sponsorship of medical schools or nurse training; sponsorship of continuing educational events, with influence on the curriculum;[109] and hiring physicians as paid consultants on medical advisory boards.

Some advocacy groups, such as No Free Lunch and AllTrials, have criticized the effect of drug marketing to physicians because they say it biases physicians to prescribe the marketed drugs even when others might be cheaper or better for the patient.[110]

There have been related accusations of disease mongering[111] (over-medicalising) to expand the market for medications. An inaugural conference on that subject took place in Australia in 2006.[112] In 2009, the Government-funded National Prescribing Service launched the "Finding Evidence – Recognising Hype" program, aimed at educating GPs on methods for independent drug analysis.[113]

Meta-analyses have shown that psychiatric studies sponsored by pharmaceutical companies are several times more likely to report positive results, and if a drug company employee is involved the effect is even larger.[114][115][116] Influence has also extended to the training of doctors and nurses in medical schools, which is being fought.

It has been argued that the design of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and the expansion of the criteria represents an increasing medicalization of human nature, or "disease mongering", driven by drug company influence on psychiatry.[117] The potential for direct conflict of interest has been raised, partly because roughly half the authors who selected and defined the DSM-IV psychiatric disorders had or previously had financial relationships with the pharmaceutical industry.[118]

In the US, starting in 2013, under the Physician Financial Transparency Reports (part of the Sunshine Act), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has to collect information from applicable manufacturers and group purchasing organizations in order to report information about their financial relationships with physicians and hospitals. Data are made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. The expectation is that the relationship between doctors and the Pharmaceutical industry will become fully transparent.[119]

In a report conducted by OpenSecrets, there were more than 1,100 lobbyists working in some capacity for the pharmaceutical business in 2017. In the first quarter of 2017, the health products and pharmaceutical industry spent $78 million on lobbying members of the United States Congress.[120]

Medication pricing

The pricing of pharmaceuticals is becoming a major challenge for health systems.[121] A November 2020 study by the West Health Policy Center stated that more than 1.1 million senior citizens in the U.S. Medicare program is expected to die prematurely over the next decade because they will be unable to afford their prescription medications, requiring an additional $17.7 billion to be spent annually on avoidable medical costs due to health complications.[122]

Regulatory issues

Ben Goldacre has argued that regulators – such as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK, or the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States – advance the interests of the drug companies rather than the interests of the public due to revolving door exchange of employees between the regulator and the companies and friendships develop between regulator and company employees.[123] He argues that regulators do not require that new drugs offer an improvement over what is already available, or even that they be particularly effective.[123]

Others have argued that excessive regulation suppresses therapeutic innovation and that the current cost of regulator-required clinical trials prevents the full exploitation of new genetic and biological knowledge for the treatment of human disease. A 2012 report by the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology made several key recommendations to reduce regulatory burdens to new drug development, including 1) expanding the FDA's use of accelerated approval processes, 2) creating an expedited approval pathway for drugs intended for use in narrowly defined populations, and 3) undertaking pilot projects designed to evaluate the feasibility of a new, adaptive drug approval process.[124]

Pharmaceutical fraud

The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2015) |

Pharmaceutical fraud involves deceptions that bring financial gain to a pharmaceutical company. It affects individuals and public and private insurers. There are several different schemes[125] used to defraud the health care system which are particular to the pharmaceutical industry. These include: Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Violations, Off Label Marketing, Best Price Fraud, CME Fraud, Medicaid Price Reporting, and Manufactured Compound Drugs.[126] Of this amount $2.5 billion was recovered through False Claims Act cases in FY 2010. Examples of fraud cases include the GlaxoSmithKline $3 billion settlement, Pfizer $2.3 billion settlement and Merck & Co. $650 million settlement. Damages from fraud can be recovered by use of the False Claims Act, most commonly under the qui tam provisions which reward an individual for being a "whistleblower", or relator (law).[127]

Every major company selling atypical antipsychotics—Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson—has either settled recent government cases, under the False Claims Act, for hundreds of millions of dollars or is currently under investigation for possible health care fraud. Following charges of illegal marketing, two of the settlements set records in 2009 for the largest criminal fines ever imposed on corporations. One involved Eli Lilly's antipsychotic Zyprexa, and the other involved Bextra, an anti-inflammatory medication used for arthritis. In the Bextra case, the government also charged Pfizer with illegally marketing another antipsychotic, Geodon; Pfizer settled that part of the claim for $301 million, without admitting any wrongdoing.[128]

In July 2012, GlaxoSmithKline pleaded guilty to criminal charges and agreed to a $3 billion settlement of the largest health-care fraud case in the U.S. and the largest payment by a drug company.[129] The settlement is related to the company's illegal promotion of prescription drugs, its failure to report safety data,[130] bribing doctors, and promoting medicines for uses for which they were not licensed. The drugs involved were Paxil, Wellbutrin, Advair, Lamictal, and Zofran for off-label, non-covered uses. Those and the drugs Imitrex, Lotronex, Flovent, and Valtrex were involved in the kickback scheme.[131][132][133]

The following is a list of the four largest settlements reached with pharmaceutical companies from 1991 to 2012, rank ordered by the size of the total settlement. Legal claims against the pharmaceutical industry have varied widely over the past two decades, including Medicare and Medicaid fraud, off-label promotion, and inadequate manufacturing practices.[134][135]

| Company | Settlement | Violation(s) | Year | Product(s) | Laws allegedly violated (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GlaxoSmithKline[136] | $3 billion | Off-label promotion/ failure to disclose safety data | 2012 | Avandia/Wellbutrin/Paxil | False Claims Act/FDCA |

| Pfizer[137] | $2.3 billion | Off-label promotion/kickbacks | 2009 | Bextra/Geodon/ Zyvox/Lyrica | False Claims Act/FDCA |

| Abbott Laboratories[138] | $1.5 billion | Off-label promotion | 2012 | Depakote | False Claims Act/FDCA |

| Eli Lilly[139] | $1.4 billion | Off-label promotion | 2009 | Zyprexa | False Claims Act/FDCA |

Physician roles

In May 2015, the New England Journal of Medicine emphasized the importance of pharmaceutical industry-physician interactions for the development of novel treatments and argued that moral outrage over industry malfeasance had unjustifiably led many to overemphasize the problems created by financial conflicts of interest. The article noted that major healthcare organizations, such as National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, the World Economic Forum, the Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, and the Food and Drug Administration had encouraged greater interactions between physicians and industry in order to improve benefits to patients.[140][141]

Response to COVID-19

In November 2020 several pharmaceutical companies announced successful trials of COVID-19 vaccines, with efficacy of 90 to 95% in preventing infection. Per company announcements and data reviewed by external analysts, these vaccines are priced at $3 to $37 per dose.[142] The Wall Street Journal ran an editorial calling for this achievement to be recognized with a Nobel Peace Prize.[143]

Doctors Without Borders warned that high prices and monopolies on medicines, tests, and vaccines would prolong the pandemic and cost lives. They urged governments to prevent profiteering, using compulsory licenses as needed, as had already been done by Canada, Chile, Ecuador, Germany, and Israel.[144]

On 20 February, 46 US lawmakers called for the US government not to grant monopoly rights when giving out taxpayer development money for any coronavirus vaccines and treatments, to avoid giving exclusive control of prices and availability to private manufacturers.[145]

In the United States, the government signed agreements in which research and development or the building of manufacturing plants for potential COVID-19 therapeutics was subsidized. Typically, the agreement involved the government taking ownership of a certain number of doses of the product without further payment. For example, under the auspices of Operation Warp Speed in the United States, the government subsidized research related to COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics at Regeneron,[146] Johnson and Johnson, Moderna, AstraZeneca, Novavax, Pfizer, and GSK. Typical terms involved research subsidies of $400 million to $2 billion, and included government ownership of the first 100 million doses of any COVID-19 vaccine successfully developed.[147]

American pharmaceutical company Gilead sought and obtained orphan drug status for remdesivir from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 23 March 2020. This provision is intended to encourage the development of drugs affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans by granting strengthened and extended legal monopoly rights to the manufacturer, along with waivers on taxes and government fees.[148][149] Remdesivir is a candidate for treating COVID-19; at the time the status was granted, fewer than 200,000 Americans had COVID-19, but numbers were climbing rapidly as the COVID-19 pandemic reached the US, and crossing the threshold soon was considered inevitable.[148][149] Remdesivir was developed by Gilead with over $79 million in U.S. government funding.[149] In May 2020, Gilead announced that it would provide the first 940,000 doses of remdesivir to the federal government free of charge.[150] After facing strong public reactions, Gilead gave up the "orphan drug" status for remdesivir on 25 March.[151] Gilead retains 20-year remdesivir patents in more than 70 countries.[144] In May 2020, the company further announced that it was in discussions with several generics companies to provide rights to produce remdesivir for developing countries, and with the Medicines Patent Pool to provide broader generic access.[152]

Developing world

Patents

Patents have been criticized in the developing world, as they are thought[who?] to reduce access to existing medicines.[153] Reconciling patents and universal access to medicine would require an efficient international policy of price discrimination. Moreover, under the TRIPS agreement of the World Trade Organization, countries must allow pharmaceutical products to be patented. In 2001, the WTO adopted the Doha Declaration, which indicates that the TRIPS agreement should be read with the goals of public health in mind, and allows some methods for circumventing pharmaceutical monopolies: via compulsory licensing or parallel imports, even before patent expiration.[154]

In March 2001, 40 multi-national pharmaceutical companies brought litigation against South Africa for its Medicines Act, which allowed the generic production of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) for treating HIV, despite the fact that these drugs were on-patent.[155] HIV was and is an epidemic in South Africa, and ARVs at the time cost between US$10,000 and US$15,000 per patient per year. This was unaffordable for most South African citizens, and so the South African government committed to providing ARVs at prices closer to what people could afford. To do so, they would need to ignore the patents on drugs and produce generics within the country (using a compulsory license), or import them from abroad. After an international protest in favour of public health rights (including the collection of 250,000 signatures by Médecins Sans Frontières), the governments of several developed countries (including The Netherlands, Germany, France, and later the US) backed the South African government, and the case was dropped in April of that year.[156]

In 2016, GlaxoSmithKline (the world's sixth largest pharmaceutical company) announced that it would be dropping its patents in poor countries so as to allow independent companies to make and sell versions of its drugs in those areas, thereby widening the public access to them.[157] GlaxoSmithKline published a list of 50 countries they would no longer hold patents in, affecting one billion people worldwide.

Charitable programs

In 2011 four of the top 20 corporate charitable donations and eight of the top 30 corporate charitable donations came from pharmaceutical manufacturers. The bulk of corporate charitable donations (69% as of 2012) comes by way of non-cash charitable donations, the majority of which again were donations contributed by pharmaceutical companies.[158]

Charitable programs and drug discovery & development efforts by pharmaceutical companies include:

- "Merck's Gift", wherein billions of river blindness drugs were donated in Africa[159]

- Pfizer's gift of free/discounted fluconazole and other drugs for AIDS in South Africa[160]

- GSK's commitment to give free albendazole tablets to the WHO for, and until, the elimination of lymphatic filariasis worldwide.

- In 2006, Novartis committed US$755 million in corporate citizenship initiatives around the world, particularly focusing on improving access to medicines in the developing world through its Access to Medicine projects, including donations of medicines to patients affected by leprosy, tuberculosis, and malaria; Glivec patient assistance programs; and relief to support major humanitarian organisations with emergency medical needs.[161]

See also

- List of industrial complexes – Economic conceptPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Big Pharma conspiracy theories – Conspiracy theories about the pharmaceutical industry

- Clinical trial – Phase of clinical research in medicine

- Drug development – Process of bringing a new pharmaceutical drug to the market

- Drug discovery – Pharmaceutical procedure

- Legal drug trade – manufacture and sale of pharmaceutical drugsPages displaying wikidata descriptions as a fallback

- List of pharmaceutical companies

- Licensed production – Production under license of technology developed elsewhere

- Outsourcing – Contracting formerly internal tasks to an external organization

- Pharmaceutical marketing – Advertising by pharmaceutical companies

- Pharmacy – Clinical health science

- Pharmacy benefit management – Administration of prescription drug programs in the United States

- Unitaid – Global health initiative

- Valuation (finance) § Valuation of intangible assets

References

- ^ McGuire, John L.; Hasskarl, Horst; Bode, Gerd; Klingmann, Ingrid; Zahn, Manuel (2007). "Pharmaceuticals, General Survey". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_273.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Bozenhardt, Erich H.; Bozenhardt, Herman F. (18 October 2018). "Are You Asking Too Much From Your Filler?". Pharmaceutical Online (Guest column). VertMarkets. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

The core mission of the pharmaceutical industry is to manufacture products for patients to cure them, vaccinate them, or alleviate a symptom, often by manufacturing a liquid injectable or an oral solid, among other therapies.

- ^ Markets, Research and (31 March 2021). "Global Pharmaceuticals Market Report 2021: Market is Expected to Grow from $1228.45 Billion in 2020 to $1250.24 Billion in 2021 - Long-term Forecast to 2025 & 2030". GlobeNewswire News Room (Press release). Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Emergence of Pharmaceutical Science and Industry: 1870-1930". Chem Eng News. 83 (25). 20 June 2005. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Sneader, Walter (31 October 2005). "13 Neurohormones". Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Nicolas (2006). "Making the First Anti-Depressant: Amphetamine in American Medicine, 1929-1950". J Hist Med Allied Sci. 61 (3): 288–323. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrj039. PMID 16492800. S2CID 24974454.

- ^ Rasmussen N (June 2008). "America's First Amphetamine Epidemic 1929–1971". Am J Public Health. 98 (6): 974–985. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.110593. PMC 2377281. PMID 18445805.

- ^ Yasiry Z, Shorvon SD (December 2012). "How phenobarbital revolutionized epilepsy therapy: the story of phenobarbital therapy in epilepsy in the last 100 years". Epilepsia. 53 (Suppl 8): 26–39. doi:10.1111/epi.12026. PMID 23205960. S2CID 8934654.

- ^ López-Muñoz F, Ucha-Udabe R, Alamo C (December 2005). "The history of barbiturates a century after their clinical introduction". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 1 (4): 329–43. PMC 2424120. PMID 18568113.

- ^ "Drug Abuse Control Amendments of 1965". NEJM (Editorial). 273 (22): 1222–1223. 25 November 1965. doi:10.1056/NEJM196511252732213.

Officers of the Food and Drug Administration, aware of the seriousness of the problem, estimate that approximately half the 9,000,000,000 barbiturate and amphetamine capsules and tablets manufactured annually in this country are diverted to illegal use. The profits to be gained from the illegal sale of these drugs have proved an attraction to organized crime, for amphetamine can be purchased at wholesale for less than $1 per 1000 capsules, but when sold on the illegal market, it brings $30 to $50 per 1000 and when retailed to the individual buyer, a tablet may bring as much as 10 to 25 cents.

- ^ "Sedative-Hypnotic Drugs — The Barbiturates — I". NEJM. 255 (24): 1150–1151. 1956. doi:10.1056/NEJM195612132552409. PMID 13378632.

The barbiturates, introduced into medicine by E. Fischer and J. von Mering in 1903, are certainly among the most widely used and abused drugs in medicine. Approximately 400 tons of these agents are manufactured each year; this is enough to put approximately 9,000,000 people to sleep each night for that period if each were given a 0.1-gm. dose

- ^ Rosenfeld L (December 2002). "Insulin: discovery and controversy". Clin Chem. 48 (12): 2270–88. doi:10.1093/clinchem/48.12.2270. PMID 12446492.

- ^ "Leading Causes of Death, 1900-1998" (PDF). CDC.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Robert N. (13 December 1999). "United States Life Tables, 1997" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. 47 (28): 1–37. PMID 10635683. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Sepkowitz, Kent A. (July 2011). "One hundred years of Salvarsan". N. Engl. J. Med. (Perspective). 365 (4): 291–3. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1105345. PMID 21793743.

- ^ Williams, KJ (1 August 2009). "The introduction of 'chemotherapy' using arsphenamine – the first magic bullet". J. R. Soc. Med. 102 (8): 343–348. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2009.09k036. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 2726818. PMID 19679737.

- ^ Aminov, Rustam I. (8 December 2010). "A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future". Front. Microbiol. 1: 134. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2010.00134. PMC 3109405. PMID 21687759.

- ^ Hager, Thomas (2006). The Demon Under the Microscope (1st ed.). New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-8213-1.

- ^ "All Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine". The Nobel Prize. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Cutler, David M.; Meara, Ellen (October 2001). Changes in the Age Distribution of Mortality Over the 20th Century (PDF) (Report). National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w8556. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b Klein, Herbert (2012). A Population History of the United States. Cambridge University Press. p. 167.

- ^ Parascandola, John (1980). The History of antibiotics: a symposium. American Institute of the History of Pharmacy No. 5. ISBN 978-0-931292-08-8.

- ^ "Diphtheria — Timelines — History of Vaccines". Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Ii, Thomas H. Maugh (13 April 2005). "Maurice R. Hilleman, 85; Scientist Developed Many Vaccines That Saved Millions of Lives". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 7 November 2014.

- ^ "Significant Dates in U.S. Food and Drug Law History". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "FDAReview.org, a project of The Independent Institute". Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Sulfanilamide Disaster". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "FDA History - Part II". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Zaffiri L, Gardner J, Toledo-Pereyra LH (April 2012). "History of antibiotics. From salvarsan to cephalosporins". J Invest Surg. 25 (2): 67–77. doi:10.3109/08941939.2012.664099. PMID 22439833. S2CID 30538825.

- ^ Hamilton-Miller JM (March 2008). "Development of the semi-synthetic penicillins and cephalosporins". Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 31 (3): 189–92. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.11.010. PMID 18248798.

- ^ Abraham EP (1987). "Cephalosporins 1945-1986". Drugs. 34 Suppl 2 (Supplement 2): 1–14. doi:10.2165/00003495-198700342-00003. PMID 3319494. S2CID 12014890.

- ^ a b Kingston W (July 2004). "Streptomycin, Schatz v. Waksman, and the balance of credit for discovery". J Hist Med Allied Sci. 59 (3): 441–62. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrh091. PMID 15270337. S2CID 27465970.

- ^ Nelson ML, Levy SB (December 2011). "The history of the tetracyclines". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1241 (1): 17–32. Bibcode:2011NYASA1241...17N. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06354.x. PMID 22191524. S2CID 34647314.

- ^ "ERYTHROMYCIN". Br Med J. 2 (4793): 1085–6. November 1952. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4793.1085. PMC 2022076. PMID 12987755.

- ^ Anderson, Rosaleen (2012). Antibacterial agents chemistry, mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and clinical applications. Oxford: WiBlackwell. ISBN 9780470972458.

- ^ Federal Trade Commission Report of Antibiotics Manufacture, June 1958 (Washington D.C., Government Printing Office, 1958) pages 98-120

- ^ Federal Trade Commission Report of Antibiotics Manufacture, June 1958 (Washington D.C., Government Printing Office, 1958) page 277

- ^ Anderson, Robert N. (13 December 1999). "United States Life Tables, 1997" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 47 (28): 1–37. PMID 10635683. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Cutler, David; Meara, Ellen (October 2001). "Changes in the Age Distribution of Mortality Over the 20th Century" (PDF). NBER Working Paper No. 8556. doi:10.3386/w8556. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Sweet BH, Hilleman MR (November 1960). "The vacuolating virus, S.V. 40". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 105 (2): 420–7. doi:10.3181/00379727-105-26128. PMID 13774265. S2CID 38744505.

- ^ Shah K, Nathanson N (January 1976). "Human exposure to SV40: review and comment". Am. J. Epidemiol. 103 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112197. PMID 174424.

- ^ "Studies:No Evidence That SV40 is Related to Cancer". Archived from the original on 28 October 2014.

- ^ "History of Vaccines — A Vaccine History Project of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia". Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Prevention of Measles, Rubella, Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and Mumps, 2013". Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Bloch AB, Orenstein WA, Stetler HC, et al. (1985). "Health impact of measles vaccination in the United States". Pediatrics. 76 (4): 524–32. doi:10.1542/peds.76.4.524. PMID 3931045. S2CID 6512947.

- ^ Insull W (January 2009). "The pathology of atherosclerosis: plaque development and plaque responses to medical treatment". The American Journal of Medicine. 122 (1 Suppl): S3 – S14. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.10.013. PMID 19110086.

- ^ Gaddam KK, Verma A, Thompson M, Amin R, Ventura H (May 2009). "Hypertension and cardiac failure in its various forms". The Medical Clinics of North America. 93 (3): 665–80. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.005. PMID 19427498. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Agabiti-Rosei E (September 2008). "From macro- to microcirculation: benefits in hypertension and diabetes". Journal of Hypertension. 26 (Suppl 3): S15–21. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000334602.71005.52. PMID 19363848.

- ^ Murphy BP, Stanton T, Dunn FG (May 2009). "Hypertension and myocardial ischemia". The Medical Clinics of North America. 93 (3): 681–95. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.003. PMID 19427499. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ White WB (May 2009). "Defining the problem of treating the patient with hypertension and arthritis pain". The American Journal of Medicine. 122 (5 Suppl): S3–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.03.002. PMID 19393824.

- ^ Truong LD, Shen SS, Park MH, Krishnan B (February 2009). "Diagnosing nonneoplastic lesions in nephrectomy specimens". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 133 (2): 189–200. doi:10.5858/133.2.189. PMID 19195963. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Tracy RE, White S (February 2002). "A method for quantifying adrenocortical nodular hyperplasia at autopsy: some use of the method in illuminating hypertension and atherosclerosis". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 6 (1): 20–9. doi:10.1053/adpa.2002.30606. PMID 11842376.

- ^ Aronow WS (August 2008). "Hypertension and the older diabetic". Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 24 (3): 489–501, vi–vii. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2008.03.001. PMID 18672184. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Gardner AW, Afaq A (2008). "Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Arterial Disease". Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 28 (6): 349–57. doi:10.1097/HCR.0b013e31818c3b96. PMC 2743684. PMID 19008688.

- ^ Novo S, Lunetta M, Evola S, Novo G (January 2009). "Role of ARBs in the blood hypertension therapy and prevention of cardiovascular events". Current Drug Targets. 10 (1): 20–5. doi:10.2174/138945009787122897. PMID 19149532. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Craig WM (1939). "Surgical Treatment of Hypertension". Br Med J. 2 (4120): 1215–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4120.1215. PMC 2178707. PMID 20782854.

- ^ Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug Discovery. A History. New York: Wiley. p. 371.

- ^ Beyer KH (1993). "Chlorothiazide. How the thiazides evolved as antihypertensive therapy". Hypertension. 22 (3): 388–91. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.22.3.388. PMID 8349332.

- ^ Borhani NO, Hechter HH (1964). "Recent Changes in CVR Disease Mortality in California: An Epidemiologic Appraisal". Public Health Rep. 79 (2): 147–60. doi:10.2307/4592077. JSTOR 4592077. PMC 1915335. PMID 14119789.

- ^ "The Lasker Foundation - Awards". Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Wright, James M.; Musini, Vijaya M.; Gill, Rupam (18 April 2018). "First-line drugs for hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (4): CD001841. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6513559. PMID 29667175.

- ^ Stason WB, Cannon PJ, Heinemann HO, Laragh JH (November 1966). "Furosemide. A clinical evaluation of its diuretic action". Circulation. 34 (5): 910–20. doi:10.1161/01.cir.34.5.910. PMID 5332332. S2CID 886870.

- ^ Black JW, Crowther AF, Shanks RG, Smith LH, Dornhorst AC (1964). "A new adrenergic betareceptor antagonist". The Lancet. 283 (7342): 1080–1081. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(64)91275-9. PMID 14132613.

- ^ Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, Craig ME, Craig JC, Strippoli GF (2012). "Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD004136. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004136.pub3. PMC 11357690. PMID 23235603.

- ^ "A brief history of the birth control pill - The pill timeline | Need to Know". PBS. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian. "Why the Oral Contraceptive Is Just Known as "The Pill"". Smithsonian Magazine. smithsonianmag.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "BBC News | HEALTH | A short history of the pill". Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "FDA's Approval of the First Oral Contraceptive, Enovid". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Cafe, Rebecca (4 December 2011). "How the contraceptive pill changed Britain". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Brochure: The History of Drug Regulation in the United States". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Tobert, Jonathan A. (July 2003). "Lovastatin and beyond: the history of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2 (7): 517–526. doi:10.1038/nrd1112. ISSN 1474-1776. PMID 12815379. S2CID 3344720.

- ^ Endo A (1 November 1992). "The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors". Journal of Lipid Research. 33 (11): 1569–82. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)41379-3. PMID 1464741.

- ^ Endo, Akira (2004). "The origin of the statins". International Congress Series. 1262: 3–8. doi:10.1016/j.ics.2003.12.099.

- ^ Scandinaviansimvastatinsurvival (November 1994). "Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S)". Lancet. 344 (8934): 1383–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90566-5. PMID 7968073. S2CID 5965882.

- ^ "National Inventors Hall of Fame Honors 2012 Inductees". PRNewswire. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "How One Scientist Intrigued by Molds Found First Statin". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Top Global Pharmaceutical Company Report - The Pharma 1000" (PDF). Torreya. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Top Global Pharmaceutical Company Report" (PDF). The Pharma 1000. November 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ a b Alvarado, Delilah; Pagliarulo, Ned (8 January 2024). "Year of biotech layoffs leaves industry looking for spark". BioPharma Dive. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ a b Bell, Jacob (20 December 2022). "Biotech M&A is picking back up. Here are the latest deal". BiopharmaDive. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Annual Impact Report". Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures Key Data 2021" (PDF). European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Outsourcing-Pharma.com (25 May 2011). "Pfizer teams with Parexel and Icon in CRO sector's latest strategic deals". Outsourcing-Pharma.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "How Many New Drugs Did FDA Approve Last Year?". pharmalot.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ "Research". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2006.

- ^ a b Perry, Susan (8 August 2012). "Donald Light and Joel Lexchin in BMJ 2012;345:e4348, quoted in: Big Pharma's claim of an 'innovation crisis' is a myth, BMJ authors say". MinnPost. Archived from the original on 11 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "About PhRMA". Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ "Has the Pharmaceutical Blockbuster Model Gone Bust?". bain.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Harper, Matthew (10 February 2012). "The Truly Staggering Cost Of Inventing New Drugs". Forbes. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ IMS Health (18 June 2015). "Are European biotechnology companies sufficiently protected?". Portal of Competitive Intelligence. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Liberti L, McAuslane JN, Walker S (2011). "Standardizing the Benefit-Risk Assessment of New Medicines: Practical Applications of Frameworks for the Pharmaceutical Healthcare Professional". Pharm Med. 25 (3): 139–46. doi:10.1007/BF03256855. S2CID 45729390. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Electronic Orange Book". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ "The Orphan Drug Act (as amended)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ "The top 20 pharma companies by 2022 revenue".

- ^ "Standardseite der Domain www.vfa.de" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ Herper, Matthew & Kang, Peter (22 March 2006). "The World's Ten Best-Selling Drugs". Forbes. Archived from the original on 5 May 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ "Creating Connected Solutions for Better Healthcare Performance". IMS Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2022.