Клавир-Убунг III

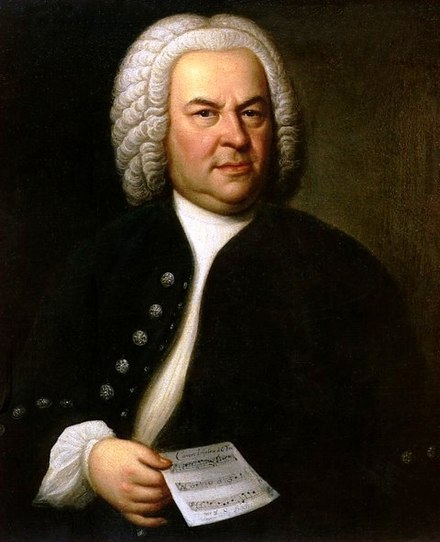

Clavier -Übung III , иногда называемая Немецкой органной мессой , представляет собой сборник произведений для органа Иоганна Себастьяна Баха , начатый в 1735–1736 годах и опубликованный в 1739 году. Он считается самым значительным и обширным произведением Баха для органа, содержащим некоторые из его самых музыкально сложных и технически сложных произведений для этого инструмента.

В своем использовании модальных форм, мотетного стиля и канонов он обращается к религиозной музыке мастеров stile antico , таких как Фрескобальди , Палестрина , Лотти и Кальдара . В то же время Бах был дальновидным, включив и переработав современные барочные музыкальные формы, такие как хорал во французском стиле. [1]

Произведение имеет форму органной мессы : между ее вступительной и заключительной частями — прелюдией и фугой «Святой Анны» в ми-бемоль мажоре, BWV 552 — находятся 21 хоральная прелюдия, BWV 669–689, включающая две части лютеранской мессы и шесть хоралов катехизиса, за которыми следуют четыре дуэта, BWV 802–805. Хоральные прелюдии варьируются от композиций для одной клавиатуры до шестичастной фугальной прелюдии с двумя частями в педали.

Цель сборника была четырехкратной: идеализированная органная программа, в которой отправной точкой были концерты для органа, данные самим Бахом в Лейпциге; практический перевод лютеранской доктрины на музыкальный язык для религиозного использования в церкви или дома; сборник органной музыки во всех возможных стилях и идиомах, как древних, так и современных, и должным образом интернационализированных; и как дидактическое произведение, представляющее примеры всех возможных форм контрапунктической композиции, выходящее далеко за рамки предыдущих трактатов по музыкальной теории. [2]

История и происхождение

_006.jpg/440px-Canaletto_(I)_006.jpg)

25 ноября 1736 года состоялось освящение нового органа, построенного Готфридом Зильберманом , в центральном и символическом месте Фрауэнкирхе в Дрездене . На следующей неделе, во второй половине дня 1 декабря, Бах дал там двухчасовой органный концерт, который получил «большие аплодисменты». Бах привык играть на церковных органах в Дрездене, где с 1733 года его сын, Вильгельм Фридеман Бах , был органистом в Софиенкирхе . Считается вероятным, что на декабрьском концерте Бах впервые исполнил части своего еще неопубликованного Clavier-Übung III , сочинение которого, согласно датировке гравюры Грегори Батлером, началось еще в 1735 году. Этот вывод был сделан из особого указания на титульном листе, что он был «подготовлен для любителей музыки и особенно знатоков» музыки; из современных сообщений о привычке Баха давать органные концерты для верующих после богослужений; и из последующей традиции среди любителей музыки в Дрездене посещать воскресные вечерние органные концерты в Фрауэнкирхе, которые давал ученик Баха Готфрид Август Гомилиус , чья программа обычно состояла из хоральных прелюдий и фуги . Бах позже жаловался, что темперация на органах Зильбермана не очень подходит для «сегодняшней практики». [3] [4] [5]

Clavier-Übung III — третья из четырёх книг Clavier-Übung Баха . Это была единственная часть музыки, предназначенная для органа, остальные три части были для клавесина. Название, означающее «клавиатурная практика», было осознанной отсылкой к давней традиции трактатов с похожими названиями: Иоганн Кунау (Лейпциг, 1689, 1692), Иоганн Филипп Кригер (Нюрнберг, 1698), Винсент Любек (Гамбург, 1728), Георг Андреас Зорге (Нюрнберг, 1739) и Иоганн Сигизмунд Шольце (Лейпциг, 1736–1746). Бах начал сочинять после завершения Clavier-Übung II — Итальянского концерта, BWV 971 и Увертюры во французском стиле, BWV 831 — в 1735 году. Бах использовал две группы граверов из-за задержек в подготовке: 43 страницы трех граверов из мастерской Иоганна Готфрида Крюгнера в Лейпциге и 35 страниц Бальтазара Шмида в Нюрнберге. Окончательная 78-страничная рукопись была опубликована в Лейпциге в Михайлов день (конец сентября) 1739 года по относительно высокой цене в 3 рейхсталера . Лютеранская тема Баха соответствовала времени, поскольку в том году в Лейпциге уже состоялось три двухсотлетних фестиваля Реформации . [6]

Dritter Theil der Clavier Übung bestehend in verschiedenen Vorspielen über die Catechismus- und ere Gesaenge, vor die Orgel: Denen Liebhabern, in besonders denen Kennern von dergleichen Arbeit, zur Gemüths Ergezung verfertiget von Иоганн Себастьян Бах, Кенигль. Полнишен и Чурфюрстль. Саехсс. Хофф-композитор, капельмейстер и директор хоровой музыки в Лейпциге. В Verlegung des Authoris.

Титульный лист Clavier-Übung III

В переводе титульный лист гласит: «Третья часть клавирных упражнений, состоящая из различных прелюдий к Катехизису и других гимнов для органа. Подготовлено для любителей музыки и особенно для знатоков такого рода произведений, для воссоздания духа, Иоганном Себастьяном Бахом, королевским польским и курфюрстским саксонским придворным композитором, капельмейстером и руководителем хора musicus , Лейпциг. Опубликовано автором». [7]

Изучение оригинальной рукописи позволяет предположить, что первыми были написаны прелюдии Kyrie-Gloria и более крупные хоральные прелюдии катехизиса, за ними в 1738 году последовали прелюдия и фуга «Святая Анна», а также хоральные прелюдии manualiter и, наконец, в 1739 году — четыре дуэта. За исключением BWV 676, весь материал был написан заново. Схема работы и ее публикация, вероятно, были мотивированы Harmonische Seelenlust (1733–1736) Георга Фридриха Кауфмана , Compositioni Musicali (1734–1735) Конрада Фридриха Хюрлебуша и хоральными прелюдиями Иеронима Флорентинуса Квеля , Иоганна Готфрида Вальтера и Иоганна Каспара Фоглера, опубликованными между 1734 и 1737 годами, а также более ранними Livres d'orgue , французскими органными мессами Николя де Гриньи (1700), Пьера Дюмажа (1707) и другими. [8] [9] Формулировка титульного листа Бахом следует некоторым из этих более ранних произведений, описывая особую форму композиций и обращаясь к «знатокам», что является его единственным отступлением от титульного листа Clavier-Übung II . [10]

Хотя Clavier-Übung III признан не просто разнородным сборником пьес, не было единого мнения о том, образует ли он цикл или является просто набором тесно связанных пьес. Как и предыдущие органные произведения этого типа таких композиторов, как Франсуа Куперен , Иоганн Каспар Керлл и Дитрих Букстехуде , он был отчасти ответом на музыкальные требования церковных служб. Ссылки Баха на итальянскую, французскую и немецкую музыку помещают Clavier-Übung III непосредственно в традицию Tabulaturbuch , похожего, но гораздо более раннего сборника Элиаса Аммербаха , одного из предшественников Баха в церкви Св. Фомы в Лейпциге. [11]

Сложный музыкальный стиль Баха критиковался некоторыми его современниками. Композитор, органист и музыковед Иоганн Маттезон заметил в "Die kanonische Anatomie" (1722): [12]

Это правда, и я сам это испытал, что быстрый прогресс... с художественными произведениями ( Kunst-Stücke ) [т. е. канонами и т. п.] может так увлечь разумного композитора, что он сможет искренне и тайно наслаждаться своим собственным произведением. Но из-за этого себялюбия мы невольно уходим от истинной цели музыки, пока не перестаем думать о других, хотя наша цель — восхищать их. На самом деле мы должны следовать не только своим собственным наклонностям, но и наклонностям слушателя. Я часто сочинял что-то, что казалось мне пустяком, но неожиданно получало большую популярность. Я мысленно отметил это и написал еще то же самое, хотя это имело мало достоинств, если судить по артистизму.

До 1731 года, за исключением его знаменитого высмеивания в 1725 году декламационного письма Баха в кантате Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 21 , комментарии Маттезона о Бахе были положительными. Однако в 1730 году он случайно услышал, что Готфрид Беньямин Ханке неблагоприятно отзывался о его собственной технике игры на клавиатуре: «Бах сыграет Маттезона в мешок и обратно». С 1731 года его тщеславие было уязвлено, и сочинения Маттезона стали критическими по отношению к Баху, которого он называл «der künstliche Bach». В тот же период бывший ученик Баха Иоганн Адольф Шайбе делал язвительные критические замечания в адрес Баха: в 1737 году он писал, что Бах «лишил свои пьесы всего естественного, придав им напыщенный и запутанный характер, и затмил их красоту слишком большим количеством искусства». [13] Шайбе и Маттесон использовали практически те же самые линии атаки на Баха; и действительно, Маттесон был напрямую вовлечен в кампанию Шайбе против Баха. Бах не комментировал это напрямую в то время: его дело было аргументировано с некоторой осторожной подсказкой от Баха Иоганном Авраамом Бирнбаумом, профессором риторики в Лейпцигском университете , любителем музыки и другом Баха и Лоренца Кристофа Мицлера . В марте 1738 года Шайбе начал новую атаку на Баха за его «немалые ошибки»:

Этот великий человек недостаточно изучил науки и гуманитарные науки, которые на самом деле требуются от ученого композитора. Как может человек, который не изучал философию и не способен исследовать и распознавать силы природы и разума, быть без изъянов в своей музыкальной работе? Как может он достичь всех преимуществ, необходимых для развития хорошего вкуса, когда он едва ли утруждал себя критическими наблюдениями, исследованиями и правилами, которые так же необходимы для музыки, как и для риторики и поэзии. Без них невозможно сочинять трогательно и выразительно.

В рекламе своего предстоящего трактата Der vollkommene Capellmeister (1739) в 1738 году Маттезон включил письмо Шайбе, полученное в результате его обмена мнениями с Бирнбаумом, в котором Шайбе выразил сильное предпочтение «естественной» мелодии Маттезона перед «искусным» контрапунктом Баха. Через своего друга Мицлера и его лейпцигских печатников Крюгнера и Брейткопфа, также печатников Маттезона, как и другие, Бах мог заранее знать содержание трактата Маттезона. Относительно контрапункта Маттезон писал:

Из двойных фуг с тремя темами, насколько мне известно, нет ничего другого в печати, кроме моей собственной работы под названием Die Wollklingende Fingerspruche, части I и II, которую из скромности я бы никому не рекомендовал. Напротив, я бы предпочел увидеть что-то в этом роде, опубликованное прославленным господином Бахом в Лейпциге, который является великим мастером фуги. Между тем, этот недостаток в изобилии обнажает не только ослабленное состояние и упадок основательных контрапунктистов, с одной стороны, но, с другой стороны, отсутствие интереса у нынешних невежественных органистов и композиторов к таким поучительным вопросам.

Какова бы ни была личная реакция Баха, контрапунктическое написание Clavier-Übung III стало музыкальным ответом на критику Шайбе и призыв Маттезона к органистам. Приведенное выше утверждение Мизлера о том, что качества Clavier-Übung III стали «мощным опровержением тех, кто рискнул критиковать музыку придворного композитора», было словесным ответом на их критику. Тем не менее, большинство комментаторов сходятся во мнении, что главным источником вдохновения для монументального опуса Баха была музыка, а именно музыкальные произведения, такие как Fiori musicali Джироламо Фрескобальди , к которым Бах питал особую привязанность, приобретя свою личную копию в Веймаре в 1714 году. [8] [14] [15]

Текстовый и музыкальный план

| БВВ | Заголовок | Литургическое значение | Форма | Ключ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 552/1 | Прелюдия | про органо плено | Э ♭ | |

| 669 | Кайри, Готт Фатер | Кайрие | cantus fermus в сопрано | Г |

| 670 | Christe, aller Welt Trost | Кайрие | ср . в теноре | С (или Г) |

| 671 | Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist | Кайрие | cf в педали ( pleno ) | Г |

| 672 | Кайри, Готт Фатер | Кайрие | 3 4 руководство пользователя | Э |

| 673 | Christe, aller Welt Trost | Кайрие | 6 4 руководство пользователя | Э |

| 674 | Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist | Кайрие | 9 8 руководство пользователя | Э |

| 675 | Allein Gott in der Höh' | Глория | трио, мануал | Ф |

| 676 | Allein Gott in der Höh' | Глория | трио, педалитер | Г |

| 677 | Allein Gott in der Höh' | Глория | трио, мануал | А |

| 678 | Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot' | Десять заповедей | см. в каноне | Г |

| 679 | Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot' | Десять заповедей | фуга, мануал | Г |

| 680 | Мы приветствуем Бога | Символ веры | à 4, в органо плено | Д |

| 681 | Мы приветствуем Бога | Символ веры | фуга, мануал | Э |

| 682 | Vater unser im Himmelreich | Молитва Господня | трио и cf в каноне | Э |

| 683 | Vater unser im Himmelreich | Молитва Господня | нефугальный, ручной | Д |

| 684 | Христос unser Herr zum Jordan Kam | Крещение | à 4, см. в педали | С |

| 685 | Христос unser Herr zum Jordan Kam | Крещение | fuga inversa , руководство пользователя | Д |

| 686 | Aus typer Noth schrei ich zu dir | Признание | à 6, в полне органо | Э |

| 687 | Aus typer Noth schrei ich zu dir | Признание | мотет, мануал | Ф ♯ |

| 688 | Иисус Христос, unser Heiland | Причастие | трио, ср. в педали | Д |

| 689 | Иисус Христос, unser Heiland | Причастие | фуга, мануал | Ф |

| 802 | Дуэт I | 3 8, незначительный | Э | |

| 803 | Дуэт II | 2 4, главный | Ф | |

| 804 | Дуэт III | 12 8, главный | Г | |

| 805 | Дуэт IV | 2 2, незначительный | А | |

| 552/2 | Фуга | 5 голосов на органо плено | Э ♭ |

Число хоральных прелюдий в Clavier-Übung III , двадцать одно, совпадает с числом частей во французских органных мессах . Настройки мессы и катехизиса соответствуют расписанию воскресного богослужения в Лейпциге, утренней мессе и дневному катехизису. В современных сборниках гимнов лютеранская месса , включающая тропные немецкие Kyrie и немецкие Gloria, подпадала под заголовок Святой Троицы. Органист и теоретик музыки Якоб Адлунг записал в 1758 году обычай церковных органистов играть два воскресных гимна « Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr » и «Wir glauben all an einen Gott» в разных тональностях: Бах использует три из шести тональностей между E и B ♭, упомянутых для «Allein Gott». Орган не играл никакой роли в экзамене по катехизису, серии вопросов и ответов о вере, поэтому наличие этих гимнов, вероятно, было личным религиозным заявлением Баха. Однако, Краткий катехизис Лютера (см. иллюстрацию) сосредоточен на Десяти заповедях, Символе веры, Молитве Господней, Крещении, Службе ключей и Исповеди, и Евхаристии, точных темах собственных шести хоралов катехизиса Лютера. В части Германии Баха эти гимны катехизиса пелись на школьных собраниях по будням, с Kyrie и Gloria по воскресеньям. Книга гимнов Лютера содержит все шесть хоралов. Однако более вероятно, что Бах использовал эти гимны, некоторые из которых были григорианского происхождения, как дань уважения основным заповедям лютеранства во время особого двухсотлетнего года проповеди Лютера 1539 года в церкви Св. Фомы в Лейпциге. Основными текстами для лютеран были Библия, книга гимнов и катехизисы: Бах уже включил многочисленные библейские тексты в свои кантаты и страсти; в 1736 году он помог подготовить книгу гимнов с Георгом Христианом Шемелли ; наконец, в 1739 году он включил гимны катехизиса (см. более раннюю иллюстрацию титульного листа) в качестве прелюдий к органному хоралу. [16]

Уильямс (1980) предположил, что Clavier-Übung III заимствовал следующие черты из «Fiori musicali» Фрескобальди , личная копия которого была подписана Бахом как «И. С. Бах 1714»:

- Намерение. Fiori были написаны «главным образом для помощи органистам» с композициями , «соответствующими мессе и вечерне».

- План. Первая из трех частей Fiori состоит из Токкаты [прелюдии] перед мессой, 2 Kyries, 5 Christes, за которыми следуют еще 6 Kyries; затем Канцона (после Послания), Ричеркаре (после Кредо), Токката Кроматика (для Вознесения) и, наконец, Канцона [фуга] (после причастия).

- Полифония. Короткие Kyries и Christes Фрескобальди написаны в четырехчастном стиле антико контрапункта. Во многих из них есть постоянно действующий cantus firmus или педальный пункт .

- Структура. Мутации и сочетание тем в фуге BWV 552/2 тесно связаны с заключительной канцоной в первом сете и альтернативным ричеркаре во втором сете Fiori . Аналогично, остинато бас фуги BWV 680 прообразован ричеркаре фугой с пятинотным остинато басом в Fiori .

По словам Уильямса (2003), Бах имел ясную литургическую цель в своем органном сборнике с его циклическим порядком и планом, понятным глазу, если не уху. Несмотря на то, что фуги manualiter были написаны в то время как Книга 2 Хорошо темперированного клавира , только последняя фуга BWV 689 имеет что-то общее. Музыкальный план Баха имеет множество структур: пьесы organum plenum; три стиля полифонии, manualiter и трио-соната в Мессе; пары в Катехизисе, две с cantus firmus в каноне, две с педальным cantus firmus , две для полного органа); и свободная инвенция в дуэтах. Фугетта BWV 681 в центре Clavier-Übung III играет структурную роль, аналогичную центральным пьесам в трех других частях Clavier-Übung Баха , чтобы отметить начало второй половины сборника. Она написана с использованием музыкальных мотивов французской увертюры , как в первой части четвертой клавирной партиты Баха BWV 828 ( Clavier-Übung I ), первой части его увертюры во французском стиле BWV 831 ( Clavier-Übung II ), шестнадцатой вариации Гольдберг-вариаций BWV 988 ( Clavier-Übung IV ), обозначенной как «Ouverture. a 1 Clav», и Contrapunctus VII в оригинальной рукописной версии «Искусства фуги» , содержащейся в P200.

Хотя Clavier-Übung III, возможно, предназначался для использования в богослужениях, техническая сложность Clavier-Übung III , как и более поздних композиций Баха — Canonic Variations BWV 769, The Musical Offering BWV 1079 и The Art of Fugue BWV 1080 — сделала бы эту работу слишком сложной для большинства органистов лютеранских церквей. Действительно, многие современники Баха намеренно писали музыку, доступную широкому кругу органистов: Зорге сочинял простые 3-голосные хоралы в своем Vorspiele (1750), потому что хоральные прелюдии, такие как у Баха, были «настолько трудны и почти непригодны для использования исполнителями»; Фогель, бывший ученик Баха из Веймара, написал свой Choräle «в основном для тех, кому приходится играть в сельских» церквях; а другой веймарский студент, Иоганн Людвиг Кребс , написал свое Klavierübung II (1737) так, чтобы на нем могла играть «дама, без особых затруднений». [17]

Clavier-Übung III сочетает в себе немецкий, итальянский и французский стили, особенно в открывающей Прелюдии, BWV 552/1, три тематические группы которой, кажется, были намеренно выбраны, чтобы представлять Францию, Италию и Германию соответственно (см. обсуждение BWV 552/1 ниже). Это отражает тенденцию в Германии конца XVII и начала XVIII века, когда композиторы и музыканты писали и исполняли в стиле, который стал известен как «смешанный вкус», фраза, придуманная Кванцем . [18] В 1730 году Бах написал ныне известное письмо городскому совету Лейпцига — его «Краткий, но самый необходимый черновик для хорошо организованной церковной музыки», — жалуясь не только на условия исполнения, но и на давление, связанное с необходимостью использовать стили исполнения из разных стран:

В любом случае, несколько странно, что от немецких музыкантов ожидают способности исполнять одновременно и экспромтом все виды музыки, независимо от того, родом она из Италии или Франции, Англии или Польши.

Уже в 1695 году в посвящении к своему Florilegium Primum Георг Муффат написал: «Я не осмеливаюсь использовать один стиль или метод, а скорее наиболее искусную смесь стилей, которую я могу создать благодаря своему опыту в разных странах... Смешивая французскую манеру с немецкой и итальянской, я начинаю не войну, а, возможно, прелюдию к единству, дорогому миру, желанному всеми народами». Эту тенденцию поощряли современные комментаторы и музыковеды, включая критиков Баха Маттезона и Шайбе, которые, восхваляя камерную музыку своего современника Георга Филиппа Телемана , писали, что «лучше всего, если сочетаются немецкое партийное письмо, итальянская галантность и французская страсть».

Вспоминая ранние годы Баха в школе Михаэлиса в Люнебурге между 1700 и 1702 годами, его сын Карл Филипп Эммануил записывает в «Некрологе» некролог Баха 1754 года:

Оттуда, благодаря частому слушанию знаменитого в то время оркестра, содержавшегося герцогом Целльским и состоявшего в основном из французов, он получил возможность укрепиться во французском стиле, который в тех краях и в то время был совершенно новым.

Придворный оркестр Георга Вильгельма, герцога Брауншвейг-Люнебургского, был создан в 1666 году и сосредоточился на музыке Жана-Батиста Люлли , которая стала популярной в Германии между 1680 и 1710 годами. Вероятно, Бах слышал оркестр в летней резиденции герцога в Данненберге близ Люнебурга. В самом Люнебурге Бах также слышал композиции Георга Бёма , органиста в церкви Иоаннискирхе, и Иоганна Фишера , посетителя в 1701 году, оба из которых находились под влиянием французского стиля. [19] Позже в Nekrolog CPE Бах также сообщает, что «в искусстве органа он взял за образцы произведения Брунса, Букстехуде и нескольких хороших французских органистов». В 1775 году он подробно рассказал об этом биографу Баха Иоганну Николаусу Форкелю, отметив, что его отец изучал не только произведения Букстехуде , Бёма , Николауса Брунса , Фишера , Фрескобальди, Фробергера , Керля , Пахельбеля , Рейнкена и Штрунка , но и «некоторых старых и хороших французов». [20]

Современные документы указывают , что среди этих композиторов были Буавен , Ниверс , Резон , д'Англебер , Корретт , Лебег , Ле Ру , Дьепар , Франсуа Куперен , Николя де Гриньи и Маршан . (Последний, согласно анекдоту Форкеля, бежал из Дрездена в 1717 году, чтобы избежать соревнования с Бахом в клавиатурной «дуэли».) [19] Сообщается , что в 1713 году при дворе Веймара принц Иоганн Эрнст , увлеченный музыкант, привез итальянскую и французскую музыку из своих путешествий по Европе. В то же время, или, возможно, раньше, Бах сделал тщательные копии всей Livre d'Orgue (1699) де Гриньи и таблицы орнаментов из Pièces de clavecin (1689) д'Англебера, а его ученик Фоглер сделал копии двух Livres d'Orgue Бойвена. Кроме того, в Веймаре Бах имел доступ к обширной коллекции французской музыки своего кузена Иоганна Готфрида Вальтера . Гораздо позже, в ходе обмена мнениями между Бирнбаумом и Шайбе по поводу композиционного стиля Баха в 1738 году, когда готовилось Clavier-Übung III , Бирнбаум поднял работы де Гриньи и Дюмажа в связи с орнаментикой, вероятно, по предложению Баха. Помимо элементов стиля «французской увертюры» в начальной прелюдии BWV 552/1 и центральной хоральной прелюдии -мануалистке BWV 681, комментаторы сходятся во мнении, что две масштабные пятичастные хоральные прелюдии — Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot' BWV 678 и Vater unser im Himmelreich BWV 682 — частично вдохновлены пятичастной фактурой Гриньи, с двумя частями в каждой мануалистке и пятой в педали. [21] [22] [23] [24] [25]

Комментаторы считают Clavier-Übung III суммой баховской техники письма для органа и в то же время личным религиозным высказыванием. Как и в других его поздних работах, музыкальный язык Баха имеет потустороннее качество, будь то модальный или конвенциональный. Композиции, написанные, по-видимому, в мажорных тональностях, такие как трио-сонаты BWV 674 или 677, тем не менее, могут иметь неоднозначную тональность. Бах сочинял во всех известных музыкальных формах: фуга, канон, парафраз, cantus firmus , ритурнель, развитие мотивов и различные формы контрапункта. [17] Существует пять полифонических композиций в стиле антико (BWV 669–671, 686 и первая часть 552/ii), показывающих влияние Палестрины и его последователей, Фукса, Кальдары и Зеленки. Однако Бах, даже используя длинные длительности нот в стиле Stile Antico , выходит за рамки оригинальной модели, как, например, в BWV 671. [17]

Уильямс (2007) описывает одну из целей Clavier-Übung III как предоставление идеализированной программы для органного концерта. Такие концерты были позже описаны биографом Баха Иоганном Николаусом Форкелем: [26]

Когда Иоганн Себастьян Бах садился за орган, когда не было богослужения, что его часто просили сделать, он обычно выбирал какую-нибудь тему и исполнял ее во всех формах органной композиции, так что тема постоянно оставалась его материалом, даже если он играл без перерыва два часа или больше. Сначала он использовал эту тему для прелюдии и фуги с полным органом. Затем он показал свое искусство, используя остановки для трио, квартета и т. д., всегда на одну и ту же тему. После этого следовал хорал, мелодия которого была игриво окружена самым разнообразным образом с первоначальной темой, в трех или четырех частях. Наконец, заключение делалось фугой с полным органом, в которой либо преобладала другая обработка только первой темы, либо одна или, в зависимости от ее характера, две другие были смешаны с ней.

Музыкальный план Clavier-Übung III соответствует этой схеме: собрание хоральных прелюдий и камерных произведений, обрамленных свободной прелюдией и фугой для органного пленума.

Нумерологическое значение

Вольф (1991) дал анализ нумерологии Clavier-Übung III . По мнению Вольфа, существует циклический порядок. Начальная прелюдия и фуга обрамляют три группы пьес: девять хоральных прелюдий, основанных на kyrie и gloria лютеранской мессы; шесть пар хоральных прелюдий на лютеранском катехизисе; и четыре дуэта. Каждая группа имеет свою собственную внутреннюю структуру. Первая группа состоит из трех групп по три. Первые три хорала на kyrie в стиле antico возвращают нас к полифоническим мессам Палестрины с все более сложными текстурами. Следующая группа состоит из трех коротких куплетов на kyrie, которые имеют прогрессивные размеры6

8,9

8, и12

8. В третьей группе из трех трио-сонат на немецком языке gloria две настройки manualiter обрамляют трио для двух мануалов и педали с регулярной прогрессией тональностей, фа мажор, соль мажор и ля мажор. Каждая пара хоралов catechism имеет настройку для двух мануалов и педали, за которой следует хорал manualiter fugal меньшего масштаба. Группа из 12 хоралов catechism далее разбита на две группы по шесть, сгруппированных вокруг основных настроек grand plenum organum ( Wir glauben и Auf tiefer Noth ). Дуэты связаны последовательной прогрессией тональностей, ми минор, фа мажор, соль мажор и ля минор. Таким образом, Clavier-Übung III объединяет множество различных структур: основные модели; похожие или контрастные пары; и постепенно увеличивающуюся симметрию. Существует также доминирующая нумерологическая символика. Девять настроек мессы (3 × 3) относятся к трем Троице в мессе, с конкретной ссылкой на Отца, Сына и Святого Духа в соответствующих текстах. Число двенадцать хоралов катехизиса можно рассматривать как ссылку на обычное церковное использование числа 12, числа учеников. Все произведение состоит из 27 пьес (3 × 3 × 3), завершающих шаблон. Однако, несмотря на эту структуру, маловероятно, что произведение когда-либо предназначалось для исполнения целиком: оно было задумано как сборник, ресурс для органистов для церковных выступлений, с дуэтами, возможно, для аккомпанемента причастию. [27]

Уильямс (2003) комментирует случаи золотого сечения в Clavier-Übung III, отмеченные различными музыковедами. Разделение тактов между прелюдией (205) и фугой (117) является одним из примеров. В самой фуге три части имеют 36, 45 и 36 тактов, поэтому золотое сечение появляется между длинами средней части и внешних частей. Середина средней части является центральной, с первым появлением там первой темы против замаскированной версии второй. Наконец, в BWV 682, Vater unser in Himmelreich (Отче наш), центральная точка, где меняются местами мануальная и педальная части, происходит в такте 41, который является суммой числового порядка букв в JS BACH (используя барочную конвенцию [28] идентификации I с J и U с V). Более поздняя каденция в такте 56 в 91-тактовой хоральной прелюдии дает еще один пример золотого сечения. 91 само по себе раскладывается на множители как 7, обозначающее молитву, умноженное на 13, обозначающее грех, два элемента — канонический закон и своенравная душа — также напрямую представлены в музыкальной структуре. [29]

Прелюдия и фуга BWV 552

- Приведенные ниже описания основаны на подробном анализе, проведенном Уильямсом (2003).

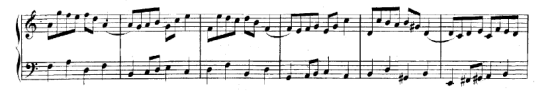

BWV 552/1 Прелюдия

Вместе с Токкатой фа мажор BWV 540 это самая длинная органная прелюдия Баха. Она сочетает в себе элементы французской увертюры (первая тема), итальянского концерта (вторая тема) и немецкой фуги (третья тема), хотя и адаптированная для органа. Есть обычные пунктирные ритмы увертюры, но чередование тем больше обязано традиции контрастных пассажей в органных композициях, чем обменам соло-тутти в концерте Вивальди. Первоначально, возможно, написанная в тональности ре мажор, более распространенной тональности для концерта или увертюры, Бах мог транспонировать ее и фугу в ми бемоль мажор , потому что Маттезон описал тональность в 1731 году как «красивую и величественную тональность», избегаемую органистами. В произведении также есть три отдельные темы (ля, си, до), иногда перекрывающиеся, что комментаторы интерпретировали как представление Отца, Сына и Святого Духа в Троице. Другие ссылки на Троицу включают три бемоля в ключевом знаке, как и сопровождающая их фуга.

По мере развития прелюдии репризы первой темы укорачиваются, как в типичном концерте Вивальди; репризы второй темы просто транспонируются на доминанту; а репризы третьей темы становятся более протяженными и развитыми. Нет никаких токкатных пассажей, и музыкальное письмо совершенно отличается от того периода. Для каждой темы педальная партия имеет разный характер: барочное бассо континуо в первой теме; квазипиццикато бас во второй; и бас в стиле антико в третьей, с чередованием нот между стопами. Все три темы разделяют трехшестую фигуру: в первой теме в такте 1 это фигура, типичная для французской увертюры; во второй теме в такте 32 это эхо в галантном итальянском стиле; а в третьей теме в такте 71 это мотив, типичный для немецких органных фуг. Три темы отражают национальные влияния: первая французская; вторая итальянская, с ее галантным письмом; и третья немецкая, со многими элементами, взятыми из традиции северогерманских органных фуг. Маркировка forte и piano во второй теме для эхо показывает, что требовалось по крайней мере два руководства; Уильямс предположил, что, возможно, подразумевалось даже три руководства, с первой темой, сыгранной на первой клавиатуре, второй и третьей на второй и эхо на третьей.

| Раздел | Бары | Описание | Длина стержня |

|---|---|---|---|

| А1 | 1–32 | Первая тема – Бог, Отец | 32 бара |

| В1 | 32 (оптимистично)–50 | Вторая тема – Бог, Сын; такт 50, один такт первой темы | 18 баров |

| А2 | 51–70 | Первая часть первой темы | 20 баров |

| С1 | 71–98 (перекрытие) | Третья тема – Святой Дух | 27 баров |

| А3 | 98 (перекрытие)–111 | Вторая часть первой темы | 14 баров |

| В2 | 111 (оптимистично)–129 | Вторая тема транспонирована на кварту вверх; такт 129, один такт первой темы | 18 баров |

| С2 | 130–159 | Третья тема с контртемой в педали | 30 баров |

| С3 | 160–173 (перекрытие) | Третья тема в B ♭ миноре | 14 баров |

| А4 | 173 (перекрытие)–205 | Повтор первой темы | 32 бара |

Первая тема: Бог, Отец

Первая тема имеет пунктирные ритмы, отмеченные лигами, французской увертюры. Она написана для пяти частей со сложными подвешенными гармониями.

Первая реприза (A2) темы в минорной тональности содержит типично французские гармонические прогрессии:

Вторая тема: Бог, Сын

Эта тема, представляющая Бога, Сына, «доброго Господа», состоит из двух тактовых фраз стаккато из трехчастных аккордов в галантном стиле с эховыми откликами, обозначенными как piano .

Далее следует более витиеватая синкопированная версия, которая не получает дальнейшего развития в прелюдии:

Третья тема: Святой Дух

Эта тема представляет собой двойную фугу , основанную на шестнадцатых нотах, представляющих «Святого Духа, нисходящего, мерцающего, как языки огня». Шестнадцатые ноты не обозначены лигами, согласно северогерманским традициям. В заключительном развитии (C3) тема переходит в ми-бемоль минор , предвещая завершение части, но также возвращаясь к предыдущему минорному эпизоду и предвосхищая подобные эффекты в более поздних частях Clavier-Übung III , таких как первый дуэт BWV 802. Двух- или трехчастное письмо в более старом стиле контрастирует с гармонически более сложным и современным письмом первой темы.

Тема шестнадцатой ноты фуги адаптирована для педали традиционным способом с использованием техники чередования ног:

BWV 552/2 Фуга

Тройная фуга... является символом Троицы. Одна и та же тема повторяется в трех связанных фугах, но каждый раз с другой личностью. Первая фуга спокойная и величественная, с абсолютно однородным движением на протяжении всей; во второй тема, кажется, замаскирована и лишь изредка узнаваема в своей истинной форме, как будто намекая на божественное принятие земной формы; в третьей она трансформируется в стремительные шестнадцатые, как будто пятидесятнический ветер с ревом идет с небес.

— Альберт Швейцер , Жан-Себастьян Бах, поэт-музыкант , 1905 г.

Фуга в ми -бемоль мажор BWV 552/2, которая завершает Clavier-Übung III, стала известна в англоязычных странах как «Святая Анна» из-за сходства первой темы с мелодией гимна с тем же названием Уильяма Крофта , мелодией, которая, вероятно, не была известна Баху. [31] Фуга в трех разделах по 36 тактов, 45 тактов и 36 тактов, причем каждый раздел представляет собой отдельную фугу на другую тему, ее называют тройной фугой . Однако вторая тема не указана точно в третьем разделе, а только явно намекается в тактах 93, 99, 102–04 и 113–14.

Число три

Число три присутствует как в Прелюдии, так и в Фуге и многими воспринимается как символ Троицы. Описание Альберта Швейцера следует традиции 19-го века, связывающей три раздела с тремя различными частями Троицы. Число три, однако, встречается много раз: в количестве бемолей ключевого знака; в количестве разделов фуги; и в количестве тактов в каждом разделе, каждый из которых кратен трем (3 × 12, 3 × 15), а также в месяце (сентябрь = 09 или 3 × 3) и году (39 или 3 × 13) публикации. Каждый из трех субъектов, кажется, вырастает из предыдущих. Действительно, музыковед Герман Келлер предположил, что второй субъект «содержится» в первом. Хотя, возможно, это скрыто в партитуре, это более очевидно для слушателя, как по их форме, так и по сходству восьмой второй темы с фигурами четвертного ряда в контртеме к первой теме. Аналогично, шестнадцатые фигуры в третьей теме можно проследить до второй темы и контртемы первой части. [32]

Форма фуги

Форма фуги соответствует форме трехчастного ричеркара или канцоны XVII века , например, у Фробергера и Фрескобальди: во-первых, в том, как темы становятся все быстрее в последовательных разделах; и, во-вторых, в том, как одна тема трансформируется в следующую. [33] [34] Баха также можно рассматривать как продолжателя лейпцигской традиции контрапунктических композиций в разделах, восходящих к клавирным ричеркарам и фантазиям Николауса Адама Штрунка и Фридриха Вильгельма Цахова . Темповые переходы между различными разделами естественны: минимы первого и второго разделов соответствуют четвертным с точкой трем.

Источник предметов

Многие комментаторы отмечали сходство между первой темой и темами фуг других композиторов. Как пример stile antico, это скорее общая тема, типичная для fuga grave тем того времени: «тихая4

2" размер такта, восходящие кварты и узкий мелодический диапазон. Как указывает Уильямс (2003), сходство с темой фуги Конрада Фридриха Хюрлебуша , которую сам Бах опубликовал в 1734 году, могло быть преднамеренной попыткой Баха ослепить свою публику наукой. Роджер Уибберли [35] показал, что основу всех трех тем фуг, а также некоторых отрывков в Прелюдии, можно найти в первых четырех фразах хорала "O Herzensangst, O Bangigkeit". Первые два раздела BWV 552/2 имеют много общего с фугой ми ♭ мажор BWV 876/2 в "Хорошо темперированном клавире " , книга 2, написанной в тот же период. В отличие от настоящих тройных фуг, таких как фа ♯ минор BWV 883 из той же книги или некоторых контрапунктов в "Искусстве Фуга , намерение Баха с BWV 552/2, возможно, не состояло в том, чтобы объединить все три темы, хотя теоретически это было бы возможно. Скорее, по мере развития работы, первая тема слышится поющей через другие: иногда скрытой; иногда, как во второй части, тихо в голосах альта и тенора; и, наконец, в последней части, высоко в дисканте и, по мере приближения кульминационного завершения, квази-остинато в педали, громоподобно прозвучавшей под двумя наборами верхних голосов. Во второй части она играется на фоне восьмых нот; и в частях последней, на фоне бегущих шестнадцатых пассажей. По мере развития фуги это создает то, что Уильямс назвал кумулятивным эффектом «массового хора». В более поздних частях, чтобы приспособиться к тройному размеру, первая тема становится ритмически синкопированной, в результате чего возникает то, что музыкальный ученый Роджер Булливант назвал «степенью ритмической сложности, вероятно, беспрецедентной в фуге любого периода».

| Раздел | Бары | Тактовый размер | Описание | Функции | Стиль |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Первый | 1–36 [36] | 4 2 | a pleno organo , 5 частей, 12 записей, контрсубъект в четвертях | Выдающиеся восходящие квартовые доли, стретти в тактах в параллельных терциях (б.21) и секстах (б.26) | Stile antico, fuga grave |

| Второй | 37–81 [45] | 6 4 | manualiter , 4 части, вторая тема, затем 15 записей объединенных первой и второй тем из б.57 | Выделение вторых и третьих, частичное сочетание первых и вторых субъектов в b.54 | Stile antico |

| Третий | 82–117 [36] | 12 8 | a pleno organo , 5 частей, третья тема, затем объединены первая и третья темы из б.87 | выдающиеся нисходящие квинтовые ноты, шестнадцатые фигуры, напоминающие вторую тему, 2 записи третьей темы и 4 записи первой темы в педальной части | Стиль модерн, жигаподобный |

Первая часть

Первая часть — тихая4

2Пятиголосная фуга в стиле антико. Контрпредмет в четвертях.

Имеется два пассажа стретто , первый в терциях (ниже), второй в секстах.

Вторая часть

Вторая часть — это двойная фуга из четырех частей на одном мануале. Вторая тема в бегущих восьмых нотах начинается на второй доле 37-го такта.

Первая тема появляется постепенно, впервые намек на нее дан во внутренних частях (такты 44–46).

затем в дисканте такта 54

прежде чем подняться из нижнего регистра как полноценный контрсубъект (такты 59–61).

Третья секция

Третья часть представляет собой пятичастную двойную фугу для полного органа. Предшествующий такт во второй части играется как три доли одного минима ( гемиола ) и, таким образом, обеспечивает новый пульс. Третья тема живая и танцевальная, напоминающая жигу, снова начинающуюся со второй доли такта. Характерный мотив из 4 шестнадцатых нот в третьей доле уже слышался в контртеме первой части и во второй теме. Бегущий шестнадцатый пассаж является ускоренным продолжением восьмого пассажа второй части; иногда он включает мотивы из второй части.

В такте 88 третья тема сливается с первой в партии сопрано, хотя и не полностью слышимой на слух. Бах с большой оригинальностью не меняет ритм первой темы, так что она становится синкопированной по тактам. Затем тема переходит во внутреннюю часть, где она, наконец, устанавливает свою естественную пару с третьей темой: два вступления третьей точно соответствуют одному вступлению первой.

Помимо финального заявления третьей темы в педальном и нижнем мануальном регистре в терциях, есть четыре квазиостинатных заявления педальной темы первой темы, напоминающие педальную часть stile antico первой части. Над педалью третья тема и ее полушестая контртема развиваются с возрастающей экспансивностью и непрерывностью. Предпоследнее вступление первой темы — канон между парящей дискантовой частью и педалью, с нисходящими полушестыми гаммами во внутренних частях. В такте 114 — вторым тактом ниже — есть кульминационная точка с финальным звучным вступлением первой темы в педали. Это подводит произведение к блестящему завершению, с уникальным сочетанием обращенного назад stile antico в педали и обращенного вперед stile moderno в верхних частях. Как комментирует Уильямс, это «величайшее окончание любой фуги в музыке».

Хоральные прелюдии BWV 669–689

- Описания хоральных прелюдий основаны на подробном анализе Уильямса (2003).

- Чтобы прослушать MIDI- запись, нажмите на ссылку .

Хоральные прелюдии BWV 669–677 (Лютеранская месса)

Эти два хорала — немецкие версии Kyrie и Gloria лютеранской missa brevis — имеют здесь особое значение, поскольку в лютеранской церкви они заменяли два первых числа мессы и пелись в начале службы в Лейпциге. Задачу прославления в музыке доктрин лютеранского христианства, которую Бах предпринял в этом наборе хоралов, он считал актом поклонения, в начале которого он обращался к Триединому Богу в тех же гимнах молитвы и хвалы, которые пела каждое воскресенье община.

— Филипп Спитта , Иоганн Себастьян Бах , 1873 г.

В 1526 году Мартин Лютер опубликовал свою Deutsche Messe , описав, как месса могла бы проводиться с использованием церковных гимнов на немецком языке, предназначенных, в частности, для использования в небольших городах и деревнях, где не говорили на латыни. В течение следующих тридцати лет по всей Германии были опубликованы многочисленные сборники гимнов на местных языках, часто в консультации с Лютером, Юстусом Йонасом , Филиппом Меланхтоном и другими деятелями немецкой Реформации . Сборник гимнов из Наумбурга 1537 года , составленный Николаусом Медлером, содержит вступительное Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit , одну из нескольких лютеранских адаптаций тропа Kyrie summum bonum: Kyrie fons bonitatus . Первая Deutsche Messe в 1525 году проводилась в Адвент, поэтому не содержала Gloria , что объясняет ее отсутствие в тексте Лютера в следующем году. Хотя в Наумбургском гимне была немецкая версия Gloria , гимн 1523 года « Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr » Николая Деция , также адаптированный из грегорианского хорала, в конечном итоге стал почти повсеместно принят по всей Германии: впервые он появился в печати с этими словами в Магдебургском гимне 1545 года Kirchengesenge Deudsch реформатора Иоганна Шпангенберга. Спустя столетие лютеранские литургические тексты и гимнодии получили широкое распространение. В Лейпциге Бах имел в своем распоряжении Neu Leipziger gesangbuch (1682) Готфрида Фопелиуса. Лютер был ярым сторонником использования искусств, особенно музыки, в богослужении. Он пел в хоре церкви Святого Георгия в Эйзенахе , где дядя Баха Иоганн Кристоф Бах был позже органистом, его отец Иоганн Амброзиус Бах был одним из главных музыкантов и где пел сам Бах, ученик той же латинской школы, что и Лютер между 1693 и 1695 годами. [36] [37] [38]

Настройки педалитера Kyrie BWV 669–671

Kyrie обычно исполнялось в Лейпциге по воскресеньям после вступительной органной прелюдии. Три монументальных педальных настройки Kyrie Баха соответствуют трем куплетам. Они находятся в строгом контрапункте в stile antico Fiori Musicali Фрескобальди . Все три имеют части одной и той же мелодии, что и их cantus firmus — в сопрано для «Бога-Отца», в среднем теноре ( en taille ) для «Бога-Сына» и в педальном басе для «Бога-Святого Духа». Хотя и имеет общие черты с вокальными настройками Kyrie Баха , например, в его Missa in F major , BWV 233 , весьма оригинальный музыкальный стиль приспособлен к органной технике, варьируясь с каждой из трех хоральных прелюдий. Тем не менее, как и в других высокоцерковных постановках хорала, сочинение Баха остается «основанным на неизменных правилах гармонии», как описано в трактате Фукса о контрапункте « Gradus ad Parnassum ». Основательность его сочинения могла быть музыкальным средством отражения «твердости веры». Как замечает Уильямс (2003), «Общим для всех трех частей является определенное плавное движение, которое редко приводит к полным каденциям или последовательному повторению, оба из которых были бы более диатоническими, чем соответствует желаемому трансцендентальному стилю».

Ниже приведен текст трех стихов версии Лютера «Kyrie» с английским переводом Чарльза Сэнфорда Терри : [39]

Кирие, Gott Vater в Ewigkeit,

groß ist dein Barmherzigkeit,

aller Ding ein Schöpfer und Regierer.

элеисон!

Christe, aller Welt Trost

uns Sünder allein du hast erlöst;

Иисус, Готтес Зон,

unser Mittler bist in dem höchsten Thron;

zu dir schreien wir aus Herzens Begier,

eleison!

Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist,

tröst', stärk' uns im Glauben

allermeist daß wir am letzten End'

fröhlich abscheiden aus diesem Elend,

eleison!

О Господи Отче во веки веков!

Мы Твоей дивной благодати поклоняемся;

Мы исповедуем Твою силу, все миры поддерживающую.

Помилуй, Господи.

О Христе, наша единственная Надежда,

Который Своей кровью искупил нас;

О Иисусе! Сын Божий!

Наш Искупитель! Наш Заступник на небесах!

Господи, к Тебе одному мы взываем в нашей нужде,

Помилуй, Господи.

Святой Господь, Боже Святой Дух!

Кто жизни и света источник,

С верой поддержи наше сердце,

Чтобы в конце концов мы с миром отошли отсюда.

Помилуй, Господи.

- BWV 669 Kyrie, Gott Vater (Кирие, Боже, Вечный Отец)

BWV 669 — хоровой мотет для двух мануалов и педали.4

2время. Четыре строки cantus firmus во фригийском ладу G играются в верхней сопрано-партии на одном мануале в полубревовых долях. Единственная фугальная тема трех других частей, двух во втором мануале и одной в педальной, играется в минимовых долях и основана на первых двух строках cantus firmus . Написание ведется в alla breve строгом контрапункте, иногда отступая от модальной тональности до B ♭ и E ♭ мажор. Даже при игре под cantus firmus контрапунктическое письмо довольно сложное. Многочисленные особенности stile antico включают инверсии, задержания, стретты, использование дактилей и canone sine pausa в конце, где тема развивается без перерыва в параллельных терциях. Как и в cantus firmus , части движутся шагами, создавая легкую плавность в хоральной прелюдии.

- BWV 670 Christe, aller Welt Trost (Христос, Утешение всего мира)

BWV 670 — хоровой мотет для двух мануалов и педали.4

2время. Четыре строки cantus firmus во фригийском ладу G играются в партии тенора ( en taille ) в одном мануале в полубревовых долях. Как и в BWV 669, единственная тема фуги трех других частей, двух во втором мануале и одной в педальной, исполняется в минимовых долях и основана на первых двух строках cantus firmus . Написание снова в основном модальное, в alla breve строгом контрапункте с похожими чертами stile antico и вытекающей из этого плавностью. В этом случае, однако, меньше обращений, фразы cantus firmus длиннее и свободнее, а другие части более широко разнесены, с пассажами canone sine pausa в секстах.

- BWV 671 Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist (Кирие, Боже Святой Дух)

BWV 671 — хоральный мотет для органа пленум и педали. Басовый cantus firmus находится в полубревах в педали с четырьмя партиями выше в клавиатуре: тенор, альт и, в исключительных случаях, две партии сопрано, что создает уникальную фактуру. Тема четырехчастной фуги в руководствах вытекает из первых двух строк cantus firmus и отвечает ее инверсией, типичной для stile antico . Мотивы восьмых в восходящих и нисходящих последовательностях, начинающиеся с дактильных фигур и становящиеся все более непрерывными, закрученными и похожими на гаммы, являются отходом от предыдущих хоральных прелюдий. Среди особенностей stile antico — движение шагами и синкопирование. Любая тенденция к тому, чтобы модальная тональность стала диатонической, нейтрализуется хроматизмом заключительного раздела, где плавные восьмые внезапно заканчиваются. В последней строке cantus firmus четвертные фигуры последовательно понижаются на полутона с драматическими и неожиданными диссонансами, напоминая похожий, но менее протяженный отрывок в конце пятичастной хоральной прелюдии O lux beata Маттиаса Векмана . Как предполагает Уильямс (2003), двенадцать нисходящих хроматических шагов кажутся мольбами, повторяющимися криками eleison — «помилуй».

Ручные настройки Kyrie BWV 672–674

Фригийская тональность — это не что иное, как наша ля минор, с той лишь разницей, что она заканчивается доминантным аккордом E–G ♯ –B, как показано в хорале Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein [Кантата 153]. Этот прием начала и окончания на доминантном аккорде может использоваться и в наши дни, особенно в тех частях, в которых концерт, симфония или соната не приходят к полному завершению... Такой тип окончания пробуждает желание услышать что-то дополнительное.

- Георг Андреас Зорге , Anleitung zur Fantasie , 1767 г. [40]

Три прелюдии хоралов manualiter BWV 672–674 представляют собой короткие фугальные композиции в рамках традиции хоральной фугетты, формы, происходящей от хорального мотета , распространенного в Центральной Германии. Иоганн Кристоф Бах , дядя Баха и органист в Эйзенахе , создал 44 такие фугетты. Считается, что краткость фугетт была продиктована ограничениями по пространству: они были добавлены в рукопись на очень поздней стадии в 1739 году, чтобы заполнить пространство между уже выгравированными настройками педалитера . Несмотря на свою длину и лаконичность, все фугетты весьма нетрадиционны, оригинальны и плавно текут, иногда с потусторонней сладостью. Как свободно составленные хоральные прелюдии, темы и мотивы фуг свободно основаны на начале каждой строки cantus firmus , который в противном случае не фигурирует напрямую. Сами мотивы развиваются независимо с тонкостью и изобретательностью, типичными для позднего контрапунктического письма Баха. Батт (2006) предположил, что набор мог быть вдохновлен циклом из пяти мануальных настроек " Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland " в Harmonische Seelenlust , опубликованном его современником Георгом Фридрихом Кауфманом в 1733 году: BWV 673 и 674 используют похожие ритмы и мотивы из двух хоральных прелюдий Кауфмана.

Кажется, что Kyries был задуман как набор, в соответствии с символикой Троицы. Это отражено в контрастных размерах такта3

4,6

8и9

8. Они также связаны гармонически: все начинаются в мажорной тональности и переходят в минорную тональность перед финальной каденцией; верхняя часть каждой фугеты заканчивается на другой ноте трезвучия ми мажор; и есть соответствие между заключительными и начальными нотами последовательных пьес. То, что Уильямс (2003) назвал «новым, трансцендентным качеством» этих хоральных фугетт, отчасти обусловлено модальным письмом. Cantus firmus во фригийском ладу ми плохо подходит для стандартных методов контрапункта, поскольку вступление субъекта в доминанте исключается ладом. Эта композиционная проблема, усугубленная выбором нот, на которых пьесы начинаются и заканчиваются, была решена Бахом, имея другие тональности в качестве доминирующих в каждой фугете. Это было отходом от устоявшихся соглашений для контрапункта во фригийском ладу, восходящих к ричеркару середины XVI века со времен Палестрины. Как заметил ученик Баха Иоганн Кирнбергер в 1771 году, «великий человек отходит от правила, чтобы сохранить хорошее сочинение». [41]

- BWV 672 Kyrie, Gott Vater (Кирие, Боже, Вечный Отец)

BWV 672 — фугетта для четырех голосов, длиной 32 такта. Хотя часть начинается в соль мажоре, преобладающий тональный центр — ля минор. Тема в пунктирных минимах (соль–ля–си) и контртема восьмой ноты взяты из первой строки cantus firmus , которая также дает материал для нескольких каденций и более поздней нисходящей восьмой фигуры (такт 8 ниже). Часть последовательного письма напоминает фугу си бемоля мажор BWV 890/2 во второй книге « Хорошо темперированного клавира ». Плавность и сладкозвучность являются результатом того, что Уильямс (2003) назвал «эффектом разжижения» простого размера такта3

4; из использования параллельных терций в удвоении подлежащего и противоподлежащего; из ясных тонов четырехчастного письма, прогрессирующего от соль мажора к ля минору, ре минору, ля минору и в конце ми мажору; и из смягчающего эффекта случайного хроматизма, уже не столь драматичного, как в заключении предыдущей хоральной прелюдии BWV 671.

- BWV 673 Christe, aller Welt Trost (Христос, Утешение всего мира)

BWV 673 — фугетта для четырёх голосов, длиной 30 тактов, в составе6

8время. Уильямс (2003) описал его как «движение огромной тонкости». Тема, длиной в три с половиной такта, происходит из первой строки cantus firmus . Мотив шестнадцатой гаммы в такте 4 также связан и значительно развит на протяжении всего произведения. Контртема, которая взята из самой темы, использует тот же синкопированный скачущий мотив, что и более ранний Jesus Christus unser Heiland BWV 626 из Orgelbüchlein , похожий на жигу-образные фигуры, которые ранее использовал Букстехуде в своей хоральной прелюдии Auf meinen lieben Gott BuxWV 179; он был интерпретирован как символ торжества воскресшего Христа над смертью. В отличие от предыдущей фугетты, письмо в BWV 673 имеет игривое ритмичное качество, но снова оно модальное, нетрадиционное, изобретательное и нешаблонное, даже если на протяжении всего времени управляется аспектами cantus firmus . Фугетта начинается в тональности до мажор, модулируется в ре минор, затем переходит в ля минор перед финальной каденцией. Текучесть исходит из множества отрывков с параллельными терциями и секстами. Оригинальные черты контрапунктического письма включают в себя разнообразие вступлений субъекта (все ноты гаммы, кроме соль), которые встречаются в стретто и в каноне.

- BWV 674 Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist (Кирие, Боже Святой Дух)

BWV 674 — фугетта для четырёх голосов, длиной 34 такта, в составе9

8время. Письмо снова гладкое, изобретательное и лаконичное, сформированное cantus firmus в ми-фригийском. Мотив восьмой ноты в третьем такте повторяется на протяжении всей части, часто в терциях и секстах, и развивается больше, чем тема восьмой ноты в первом такте. Постоянная текстура восьмой ноты может быть отсылкой к последнему eleison в распевах. Часть начинается в соль мажоре, переходя в ля минор, затем кратко в до мажор, прежде чем вернуться в ля минор перед финальной каденцией в трезвучие ми мажор. Как объясняет Уильямс (1980), [29] «Так называемая модальность заключается в своего рода диатонической двусмысленности, иллюстрируемой каденцией, предложенной ключевым знаком и подтвержденной видами линий и имитаций».

Аллейн Готт в дер Хё BWV 675–677

Почти всегда Бах использует мелодию, чтобы выразить поклонение ангельских сонмов, а в масштабных пассажах изображает их сонмы, восходящие и нисходящие между землей и небом.

- Чарльз Сэнфорд Терри , Хоралы Баха, 1921 [42]

Господин Крюгнер из Лейпцига был представлен и рекомендован мне капельмейстером Бахом, но ему пришлось отпроситься, так как он принял пьесы Кауфмана для публикации и не сможет завершить их в течение долгого времени. К тому же расходы слишком высоки.

— Иоганн Готфрид Вальтер , письмо, написанное 26 января 1736 года [43]

Три варианта немецкого гимна Gloria/Trinity Allein Gott in der Höh' Баха снова намекают на Троицу: в последовательности тональностей — F, G и A — возможно, отголосок в начальных нотах первого варианта BWV 675; в размерах тактов; и в количестве тактов, отведенных для различных разделов частей. [44] Три хоральные прелюдии дают три совершенно разных трактовки: первая — мануальное трио с cantus firmus в альте; вторая — педалиральное трио-соната с намеками на cantus firmus в педали, по стилю похожее на шесть трио-сонат Баха для органа BWV 525–530; и последняя — трехчастная мануальная фугетта с темами, полученными из первых двух строк мелодии. Более ранние комментаторы считали некоторые из настроек «не совсем достойными» своего места в Clavier-Übung III , в частности, «много оклеветанную» BWV 675, которую Герман Келлер считал, что она могла быть написана во время пребывания Баха в Веймаре . [45] Более поздние комментаторы подтвердили, что все три пьесы соответствуют общим принципам, принятым Бахом для сборника, в частности, их нетрадиционность и «странность» контрапункта. Уильямс (2003) и Батт (2006) указали на возможное влияние современников Баха на его музыкальный язык. Бах был знаком с восемью версиями Allein Gott своего кузена Иоганна Готфрида Вальтера, а также с Harmonische Seelenlust Георга Фридриха Кауфмана , посмертно напечатанными лейпцигским издателем Баха Крюгнером. В BWV 675 и 677 есть сходство с некоторыми из нововведений Кауфмана : триоли против дуолей в первом; и явная артикуляция отдельными восьмыми во втором. Общий стиль BWV 675 сравнивали с обработкой Кауфмана Nun ruhen alle Wälder ; стиль BWV 676 — с квинтой собственных обработок Вальтера Allein Gott ; а BWV 677 имеет много общих деталей с фугетой Кауфмана на тему Wir glauben all an einen Gott .

Ниже приведен текст четырех стихов лютеровской версии « Глории» с английским переводом Чарльза Сэнфорда Терри : [39]

Аллейн Готт в der Höh 'sei Ehr'

und Dank für seine Gnade,

дарум дасс нун и ниммермер инс рурен канн кеин Шаде

.

ein Wohlgefall'n Gott uns Hat,

nun ist Groß Fried' on Unterlaß,

all' Fehd' Hat nun ein Ende.

Wir loben, preis'n, anbeten dich

für deine Ehr'; когда мы ели,

ты

должен был зарегистрироваться на всех Ванкенах.

ganz ungemeßn ist deine Macht,

fort g'schieht, был dein Will' Hat Bedacht;

wohl uns des feinen Herren!

О Иисус Христос, Sohn eingebor'n

deines hismlischen Vaters,

versöhner der'r, die war'n verlor'n,

du Stiller unsers Haders,

Lamm Gottes, heil'ger Herr und Gott,

nimm an die Bitt' von unsrer Нет,

erbarm ' dich unser aller!

O Heil'ger Geist, du höchstes Gut,

du allerheilsamst' Tröster,

vor's Teufels G'walt fortan behüt',

die Иисус Христос erlöset

durch große Mart'r и выпь Тод,

отбрось все несерьезные Jamm'r und Not!

darauf wir uns verlaßen.

Богу на небесах вся слава,

И благодарение, что Он так милостив,

Что отныне и во веки веков

Никакое зло не будет угнетать нас:

Его слово возвещает благоволение людям,

На земле снова восстановлен мир

Через Иисуса Христа, нашего Спасителя.

Мы смиренно поклоняемся Тебе, и хвалим,

И восхваляем за Твою великую славу:

Отче, Твое царство длится вечно,

Не хрупко и не преходяще:

Твоя сила бесконечна, как Твоя хвала,

Ты говоришь, вселенная повинуется:

В таком Господе мы счастливы.

О Иисус Христос, восседающий на престоле на небесах,

Сын Отца возлюбленный,

Которым потерянные грешники приближаются,

И вина и проклятие удаляются;

Ты, Агнец, однажды закланный, наш Бог и Господь,

К нуждающимся молитвам Твое ухо прислушивается,

И ко всем нам помилуй.

О, Утешитель, Боже, Дух Святой,

Ты источник утешения,

От власти сатаны Ты, мы верим,

Защитишь общину Христа,

Его вечную истину утвердишь,

Все зло милостиво отвратишь,

Приведешь нас к вечной жизни.

- BWV 675 Allein Gott in der Höh (Вся слава вышнему Богу)

BWV 675, 66 тактов в длину, двухчастная инвенция для верхнего и нижнего голоса с cantus firmus в партии альта. Две внешние части замысловаты и ритмически сложны с широкими скачками, контрастирующими с cantus firmus , который движется плавно шагами в минимах и четвертях.3

4Размер такта был принят как одна из ссылок в этой части на Троицу. Как и в двух предыдущих хоральных прелюдиях, здесь нет явного обозначения manualiter , только двусмысленное «a 3»: исполнителям предоставляется выбор играть на одной клавиатуре или на двух клавиатурах с педалью 4 фута (1,2 м), единственная трудность возникает из-за триолей в такте 28. [46] Часть представлена в форме тактов (AAB) с длинами тактов секций, делящимися на 3: 18-тактовый stollen имеет 9 тактов с cantus firmus и без него , а 30-тактовый abgesang имеет 12 тактов с cantus firmus и 18 без него. [47] Тема инвенции представляет собой предымитацию cantus firmus , включающую те же ноты и длины тактов, что и каждая соответствующая фаза. Дополнительные мотивы в теме изобретательно развиваются на протяжении всей пьесы: три восходящие начальные ноты; три нисходящие триоли в такте 2; прыгающие октавы в начале такта 3; и восьмая фигура в такте 4. Они игриво сочетаются постоянно меняющимися способами с двумя мотивами из контртемы — триольной фигурой в конце такта 5 и шестнадцатой гаммой в начале такта 6 — и их обращениями. В конце каждого stollen и abgesang сложность внешних частей уменьшается, с простыми триольными нисходящими гаммами в сопрано и восьмыми в басе. Гармонизация похожа на ту, что в Лейпцигских кантатах Баха, с переключением тональностей между мажором и минором.

- BWV 676 Allein Gott in der Höh (Вся слава небесному Богу)

BWV 676 — трио-соната для двух клавиатур и педали, длиной 126 тактов. Мелодия гимна вездесуща в cantus firmus , парафраз в теме верхних частей и в гармонии. Стиль композиции и детали — очаровательные и галантные — похожи на таковые в трио-сонатах для органа BWV 525–530. Хоральная прелюдия приятна для слуха, что противоречит ее технической сложности. Она отходит от трио-сонат тем, что имеет форму ритурнели, продиктованную строками cantus firmus , которая в данном случае использует более ранний вариант с последней строкой, идентичной второй. Эта особенность и длина самих строк объясняют необычную длину BWV 676.

Музыкальную форму BWV 676 можно проанализировать следующим образом:

- Такты 1–33: экспозиция, левая рука следует за правой, первые две строки cantus firmus исполняются левой рукой в тактах 12 и 28.

- такты 33–66: повтор экспозиции, правая и левая руки попеременно

- 66–78 такты: эпизод с синкопированными сонатными фигурами

- такты 78–92: третья и четвертая строки cantus firmus в каноне между педалью и каждой из двух рук, с контртемой, полученной из темы трио в другой руке

- такты 92–99: эпизод, аналогичный отрывку в первой экспозиции

- Такты 100–139: последняя строка cantus firmus в левой руке, затем в правой руке, педаль и, наконец, в правой руке, перед финальной точкой педали, над которой тема трио возвращается в правой руке на фоне чешуйчатых фигур в левой руке, создавая несколько неопределенную концовку:

- BWV 677 Allein Gott in der Höh (Вся слава вышнему Богу)

BWV 677 — двойная фугетта длиной в 20 тактов. В первых пяти тактах первая тема, основанная на первой строке cantus firmus , и контртема звучат в стретто, с ответом в тактах с 5 по 7. Оригинальность сложной музыкальной фактуры создается всеобъемлющими, но ненавязчивыми отсылками к cantus firmus и плавным мотивом шестнадцатой ноты из первой половины такта 3, который повторяется на протяжении всего произведения и контрастирует с отстраненными восьмыми нотами первой темы.

Контрастная вторая тема, основанная на второй строке cantus firmus , начинается в партии альта на последней восьмой ноте такта 7:

Две темы и мотив шестнадцатой ноты объединяются с такта 16 до конца. Примерами музыкальной иконографии являются минорное трезвучие в начальной теме и нисходящие гаммы в первой половине такта 16 — ссылки на Троицу и небесное воинство .

Хоральные прелюдии BWV 678–689 (хоралы катехизиса Лютера)

Тщательное изучение оригинальной рукописи показало, что первыми были выгравированы большие хоральные прелюдии с педалью, включая те, что были в шести гимнах катехизиса. Меньшие мануальные настройки гимнов катехизиса и четыре дуэта были добавлены позже в оставшиеся пробелы, причем первые пять гимнов катехизиса были оформлены как трехчастные фугетты, а последний — как более длинная четырехчастная фуга. Возможно, что Бах, чтобы сделать сборник более доступным, задумал эти дополнения как пьесы, которые можно было бы исполнять на домашних клавишных инструментах. Однако даже для одной клавиатуры они представляют трудности: в предисловии к своему собственному сборнику хоральных прелюдий, опубликованному в 1750 году, органист и композитор Георг Андреас Зорге писал, что «прелюдии к хоралам катехизиса господина капельмейстера Баха в Лейпциге являются примерами такого рода клавирных произведений, которые заслуживают той большой известности, которой они пользуются», добавляя, что «такие произведения настолько трудны, что практически непригодны для молодых начинающих и других, у кого нет необходимого для них значительного мастерства». [48]

Десять заповедей BWV 678, 679

- BWV 678 Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot (Это десять святых заповедей)

Ниже приведен текст первого куплета гимна Лютера с английским переводом Чарльза Сэнфорда Терри : [39]

Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot, | Это святые десять заповедей, |

Прелюдия написана в миксолидийском ладу G, заканчивается плагальной каденцией в G минор. Ритурнель находится в верхних партиях и басе в верхнем мануале и педали, с cantus firmus в каноне в октаве в нижнем мануале. Есть эпизоды ритурнели и пять записей Cantus firmus, что дает количество заповедей. Распределение партий, две партии в каждой клавиатуре и одна в педали, похоже на распределение партий в Livre d'Orgue де Гриньи , хотя Бах предъявляет гораздо более высокие технические требования к партии правой руки.

Комментаторы рассматривали канон как представление порядка, с каламбуром на канон как «закон». Как также выражено в стихах Лютера, два голоса канона рассматривались как символ нового закона Христа и старого закона Моисея, которые он повторяет. Пасторальное качество в органном письме для верхних голосов в начале было истолковано как представление безмятежности до грехопадения человека ; за ним следует беспорядок греховного своенравия; и, наконец, порядок восстанавливается в заключительных тактах со спокойствием спасения.

Верхняя часть и педаль участвуют в сложной и высокоразвитой фантазии, основанной на мотивах, введенных в ритурнель в начале хоральной прелюдии. Эти мотивы повторяются либо в своей первоначальной форме, либо в инвертированном виде. В верхней части шесть мотивов:

- три четверти в начале такта 1 выше

- пунктирный минимум во второй части такта 1 выше

- фигура из шести восьмых нот в двух половинах такта 3 выше

- фраза из трех шестнадцатых и двух пар «вздыхающих» восьмых в такте 5 выше

- полушестой пассаж во второй половине такта 5 выше

- отрывок шестнадцатой ноты во второй половине второго такта ниже (впервые звучит в такте 13)

и пять в басу:

- три четверти в начале такта 4 выше

- два четвертных с понижением на октаву в начале такта 5 выше

- фраза во второй части такта 5 выше

- трехнотная гамма во второй, третьей и четвертой четверти такта 6 выше

- последние три четверти в такте 7 выше.

Написание для двух верхних голосов похоже на написание для инструментов obligato в кантате: их музыкальный материал независим от хорала, начальная педаль G, с другой стороны, может быть услышана как предвкушение повторяющихся G в cantus firmus. Между тем cantus firmus поется в каноне в октаве на втором мануале. Пятое и последнее вступление cantus firmus находится в дальней тональности B ♭ мажор (соль минор): оно выражает чистоту Kyrie eleison в конце первого куплета, что приводит прелюдию к гармоничному завершению:

- BWV 679 Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot (Это десять святых заповедей)

Живая фугетта, похожая на жигу, имеет несколько сходств с более крупной хоральной прелюдией: она написана в миксолидийском ладу G; начинается с педального пункта повторяющихся G; число десять встречается как число вступлений темы (четыре из них перевернуты); и пьеса заканчивается плагальной каденцией. Мотивы во второй половине второго такта и контрсюжета широко развиты. Живость фугетты была воспринята как отражение увещевания Лютера в Малом катехизисе «радостно делать то, что Он заповедал». Столь же хорошо Псалом 119 говорит о «удовольствии... в Его уставах» и радости в Законе.

Символ веры BWV 680, 681

- BWV 680 Wir glauben all' an einen Gott (Мы все верим в одного Бога)

Ниже приведен текст первого куплета гимна Лютера с английским переводом Чарльза Сэнфорда Терри : [39]

Wir glauben all' an einen Gott, | Мы все верим в Единого истинного Бога, |

Хоральная прелюдия в четырех частях представляет собой фугу в дорийском ладу D, с темой, основанной на первой строке гимна Лютера. Выдающаяся контртема впервые слышится в педальном басе. По словам Питера Уильямса , хоральная прелюдия написана в итальянском стиле stilo antico, напоминающем Джироламо Фрескобальди и Джованни Баттиста Бассани . Итальянские элементы очевидны в структуре трио-сонаты, которая объединяет верхние фугальные части с остинатным фигурным басом; и в изобретательном использовании всего спектра итальянских мотивов шестнадцатых нот. Пять нот в оригинальном гимне для вступительной мелизмы на Wir расширены в первых двух тактах, а оставшиеся ноты используются для контртемы. Исключительно отсутствует cantus firmus , вероятно, из-за исключительной длины гимна. Однако черты остальной части гимна пронизывают письмо, в частности, гаммообразные пассажи и мелодические скачки. Контртема фуги адаптирована к педали как энергичный шагающий бас с попеременной работой ног; ее квазиостинатный характер последовательно интерпретировался как представляющий «твердую веру в Бога»: шагающая басовая линия часто использовалась Бахом для движений Credo , например, в Credo и Confiteor Мессы си минор . После каждого появления контртемы остинатного в педали идет переходный полушестнадцатый проход (такты 8–9, 19–20, 31–32, 44–45, 64–66), в котором музыка модулируется в другую тональность, в то время как три верхние партии играют в обратимом контрапункте : таким образом, три различные мелодические линии могут свободно меняться между тремя голосами. Эти весьма оригинальные переходные отрывки акцентируют работу и придают связность всему движению. Хотя добавленная G ♯ затрудняет узнавание мелодии хорала, ее можно услышать более отчетливо позже, поющей в партии тенора. В финальном эпизоде manualiter (такты 76–83) остинато педальные фигуры ненадолго подхватываются партией тенора, прежде чем движение подходит к концу на заключительном расширенном повторении контртемы фуги в педали. [49] [50] Американский музыковед Дэвид Йерсли описал прелюдию к хоралу следующим образом: [51] «Этот энергичный, синкопированный контрапункт разрабатывается над повторяющейся двухтактовой темой в педали, которая действует как ритурнель, чьи постоянные повторения разделены длительными паузами. Остинато остается постоянным при различных изменениях тональности, которые представляют его как в мажорном, так и в минорном ладу [...] Форма линии педали предполагает архетипическое повествование о восхождении и нисхождении в идеальной симметрии [...] Фигура с силой проецирует движения ног в церковь; услышанная на полном органе ( In Organo pleno , согласно собственному исполнительскому руководству Баха) с регистрацией всей должной серьезности , ноги движутся с реальной целью [...] Wir glauben all' — поистине пьеса для пешеходов на органе».

Американский музыковед Дэвид Йерсли описал прелюдию к хоралу следующим образом: [51] «Этот энергичный, синкопированный контрапункт разрабатывается над повторяющейся двухтактовой темой в педали, которая действует как ритурнель, чьи постоянные повторения разделены длительными паузами. Остинато остается постоянным при различных изменениях тональности, которые представляют его как в мажорном, так и в минорном ладу [...] Форма линии педали предполагает архетипическое повествование о восхождении и нисхождении в идеальной симметрии [...] Фигура с силой проецирует движения ног в церковь; услышанная на полном органе ( In Organo pleno , согласно собственному исполнительскому руководству Баха) с регистрацией всей должной серьезности , ноги движутся с реальной целью [...] Wir glauben all' — поистине пьеса для пешеходов на органе».

- BWV 681 Wir glauben all' an einen Gott (Мы все верим в одного Бога)

Manualiter fughetta in E minor является как самой короткой частью в Clavier-Übung III, так и точной серединой сборника. Тема парафразирует первую строку хорала; двухтактовый проход позже в части, ведущий к двум драматическим уменьшенным септаккордам, построен на второй строке хорала. Хотя это не строго французская увертюра, часть включает в себя элементы этого стиля, в частности, пунктирные ритмы. Здесь Бах следует своему обычаю начинать вторую половину большой коллекции с части во французском стиле (как в трех других томах Clavier-Übung , в обоих томах Das Wohltemperierte Clavier , в ранней рукописной версии Die Kunst der Fuge и в группе из пяти пронумерованных канонов в Musikalisches Opfer ). Она также дополняет предыдущую хоральную прелюдию, следуя итальянскому стилю с контрастирующим французским. Хотя произведение, очевидно, написано для органа, по стилю оно больше всего напоминает Жигу для клавесина из Первой французской сюиты ре минор BWV 812.

Молитва Господня BWV 682, 683

- BWV 682 Vater unser im Himmelreich (Отче наш, сущий на небесах )

Ниже приведен текст первого куплета гимна Лютера с английским переводом Чарльза Сэнфорда Терри : [39]

Vater unser im Himmelreich,

der du uns alle heissest gleich

Brüder sein und dich rufen

and and willst das Beten vor uns ha'n,

gib, dass nicht bet allein der Mund,

hilf, dass es geh' aus Herzensgrund.

Отче наш на небесах, Кто еси,

Кто говорит всем нам в сердце

быть братьями и взывать к Тебе,

И ты будешь молиться от всех нас,

Даруй, чтобы не только уста молились, Но

и из глубины сердца помоги ему найти путь.

Также и Дух подкрепляет нас в немощах наших; ибо мы не знаем, о чем молиться, как должно, но Сам Дух ходатайствует за нас воздыханиями неизреченными.

— Римлянам 8:26

Vater unser im Himmelreich BWV 682 in E minor долгое время считалась самой сложной из хоральных прелюдий Баха, трудной как для понимания, так и для исполнения. Благодаря ритурнельной трио-сонате в современном французском стиле galante немецкий хорал первого куплета слышится в каноне в октаве, почти подсознательно, играемый каждой рукой вместе с инструментальным соло obligato. Бах уже освоил такую сложную форму в хоровой фантазии, открывающей его кантату Jesu, der du meine Seele, BWV 78. Канон мог быть ссылкой на Закон, следование которому Лютер считал одной из целей молитвы.

Стиль galante в верхних частях отражается в их ломбардских ритмах и отдельных шестнадцатых триолях, иногда играемых против шестнадцатых, типичных для французской флейтовой музыки того времени. Ниже педаль играет беспокойное континуо с постоянно меняющимися мотивами. С технической стороны, предложение немецкого музыковеда Германа Келлера о том, что BWV 682 требует четырех мануалов и двух исполнителей, не было принято. Однако, как подчеркивал Бах своим ученикам, артикуляция имеет первостепенное значение: пунктирные фигуры и триоли должны быть различимы и должны соединяться только тогда, когда «музыка чрезвычайно быстра».

Тема в верхних частях — это сложная колоратурная версия гимна, как инструментальные соло в медленных частях трио-сонат или концертов. Ее блуждающая, вздыхающая природа была воспринята как представление неспасенной души в поисках защиты Бога. Она имеет три ключевых элемента, которые широко развиты в прелюдии: ломбардные ритмы в такте 3; хроматическая нисходящая фраза между тактами 5 и 6; и отдельные шестнадцатые триоли в такте 10. Бах уже использовал ломбардные ритмы в начале 1730-х годов, в частности, в некоторых ранних версиях Domine Deus мессы си минор из его кантаты Gloria in excelsis Deo, BWV 191. Возвышающиеся ломбардные фигуры были интерпретированы как представление «надежды» и «доверия», а мучительный хроматизм — как «терпения» и «страдания». В кульминации произведения в такте 41 хроматизм достигает своего наибольшего предела в верхних частях, когда ломбардные ритмы переходят к педали:

Потусторонний способ, которым сольные партии переплетаются вокруг сольных линий хорала, почти скрывая их, навел некоторых комментаторов на мысль о «стонах, которые не могут быть произнесены» — мистической природе молитвы. После своего первого утверждения ритурнель повторяется шесть раз, но не как строгий повтор, вместо этого порядок, в котором слышны различные мотивы, постоянно меняется. [52]

- BWV 683 Vater unser im Himmelreich (Отче наш, сущий на небесах)

Хоральная прелюдия manualiter BWV 683 в дорийском ладу D по форме похожа на более раннее сочинение Баха BWV 636 на ту же тему из Orgelbüchlein ; отсутствие педальной партии обеспечивает большую свободу и интеграцию частей в последнем произведении. Cantus firmus исполняется без перерыва в самой верхней части, в сопровождении трехголосного контрапункта в нижних частях. В аккомпанементе используются два мотива: пять нисходящих шестнадцатых в первом такте, происходящих от четвертой строки хорала "und willst das beten von uns han" (и желает, чтобы мы молились); и трех восьмых в партии альта во второй половине такта 5. Первый мотив также инвертирован. Тихая и сладостно-гармоничная природа музыки вызывает ассоциации с молитвой и созерцанием. Его интимный масштаб и ортодоксальный стиль создают полную противоположность предыдущей «большой» настройке в BWV 682. В начале каждой строки хорала музыкальная фактура урезана, и к концу строки добавляется больше голосов: самая длинная первая нота хорала идет без сопровождения. Прелюдия приходит к приглушенному завершению в нижних регистрах клавиатуры.

Крещение BWV 684, 685

- BWV 684 Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam (Христос, Господь наш, к Иордану пришел)

Ниже приведен текст первого и последнего куплетов гимна Лютера « Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam » с английским переводом Чарльза Сэнфорда Терри : [39]

Христос unser Herr zum Jordan kam

nach seines Vaters Willen,

von Sanct John die Taufe nahm,

sein Werk und Amt zu 'rfüllen,

Da wollt er stiften uns ein Bad,

zu Waschen uns von Sünden,

ersaüfen auch den выпь Tod

durch sein sein selbst Blut und Вунден;

es galt ein neues Leben.

Das Aug allein das Wasser sieht,

wie Menschen Wasser gießen;

der Glaub im Geist die Kraft versteht

des Blutes Jesu Christi;

И это для меня ein rote Flut,

von Christi Blut gefärbet,

die allen Schaden heilen tut,

von Adam her beerbet,

auch von uns selbst Begingen.

На Иордан, когда ушел наш Господь,

по воле Отца Своего,

Он принял крещение Святого Иоанна,

исполнив Свою работу и задачу;

Там Он назначил купание,

Чтобы омыть нас от скверны,

И также утопить эту жестокую Смерть

В Своей крови осквернения:

Это была не что иное, как новая жизнь.

Глаз видит только воду,

Как из руки человека она течет;

Но внутренняя вера знает невыразимую силу

Крови Иисуса Христа.

Вера видит в ней красный поток,

С кровью Христа окрашенной и смешанной,

Которая исцеляет все виды ран,

От Адама сошедшая сюда,

И нами самими наведенная на нас.