William Sims

William Sims | |

|---|---|

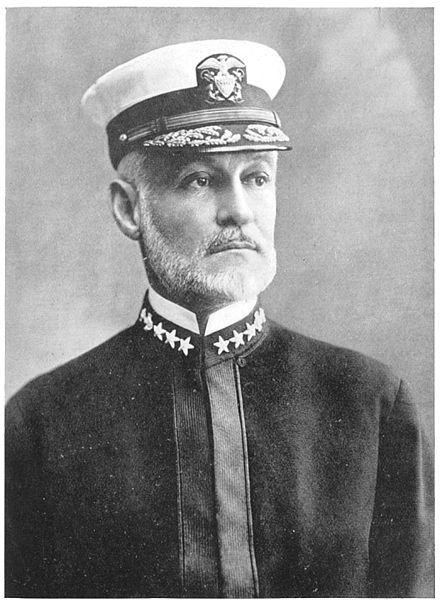

Vice Admiral William Sowden Sims | |

| Birth name | William Sowden Sims |

| Born | (1858-10-15)October 15, 1858 Port Hope, Canada West |

| Died | September 28, 1936(1936-09-28) (aged 77) Boston, Massachusetts, US |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1880–1922 |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Commands | Naval War College U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters (WWI) |

| Battles / wars | World War I |

| Awards | Navy Distinguished Service Medal |

| Other work | Pulitzer Prize for History |

William Sowden Sims (October 15, 1858 – September 28, 1936) was an admiral in the United States Navy who fought during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to modernize the navy. During World War I, he commanded all United States naval forces operating in Europe. He also served twice as president of the Naval War College.

Career

Sims was born to American father Alfred William (1826–1895) and Canadian mother Adelaide (née Sowden; b. 1835)[1] living in Port Hope, Canada West. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1880, the beginnings of an era of naval reform and greater professionalization. Commodore Stephen B. Luce founded the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island in 1884, to be the service's professional school. During the same era, Naval War College instructor Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan was writing influential books on naval strategy and sea power.

In March 1897, shortly after his promotion to lieutenant, Sims was assigned as the military attaché to Paris and St. Petersburg. In this position he became aware of naval technology developments in Europe as well gaining familiarity with European politics which would greatly assist him during World War I. He was in this assignment during the Spanish–American War during which Sims was able to use his diplomatic connections to gain information on Spain and its high-ranking officials.

Gunnery

As a young officer, Sims sought to reform naval gunnery by improving target practice. His superiors resisted his suggestions, failing to see the necessity. He was also hindered by his low rank. In 1902, Sims wrote directly to President Theodore Roosevelt. The president, who had previously served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, was intrigued by Sims' ideas and made him the Navy's Inspector of Naval Gunnery on November 5, 1902, shortly after which Sims was promoted to lieutenant commander. He was promoted to commander in 1907.

From 1911 to 1912, Sims attended the Naval War College. Promoted to captain in 1911, he became Commander, Atlantic Destroyer Flotilla in July 1913.

On March 11, 1916, Sims became the first captain of the battleship USS Nevada. Nevada was the largest, most modern and most powerful ship in the U.S. Navy at that time. His selection as her captain shows the esteem in which he was held in the Navy.[2]

First World War

Shortly before the United States entered World War I, then Rear Admiral Sims was assigned as the president of the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island in February 1917. Just before the U.S. entered the war, the Wilson administration sent him to London as the senior naval representative. After the U.S. entry in April 1917, Sims was given command over U.S. naval forces operating from Britain. He received a temporary promotion (brevet) to vice admiral in May 1917.

The major threat he faced was a highly effective German submarine campaign against freighters bringing vital food and munitions to the Allies. The combined Anglo-American naval war against U-boats in the western approaches to the British Isles in 1917–18 was a success due to the ability of Sims to work smoothly with his British counterpart, Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly.[3]

Sims believed the Navy Department in Washington, which was effectively headed by Assistant Secretary Franklin D. Roosevelt, was failing to provide him with sufficient authority, information, autonomy, manpower, and naval forces.

He ended the war as a vice admiral, in command of all U.S. naval forces operating in Europe. Shortly after the Armistice , Sims was promoted to temporary admiral in December 1918 but reverted to his permanent rank of rear admiral in April 1919 when he was assigned as president of the Naval War College.

Attack on Daniels

In 1919 after the war ended in Allied victory, Sims publicly attacked the deficiencies of American naval strategy, tactics, policy, and administration. He charged the failures had cost the Allies 2,500,000 tons of supplies, thereby prolonging the war by six months. He estimated the delay had raised the cost of the war to the Allies by $15 billion, and that it led to the unnecessary loss of 500,000 lives. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels was more of a politician than a naval strategist, so he ably countered the accusations. He pointed to Sims' anglophilism, and said his vantage point in London was too narrow to assess accurately the overall war effort by the U.S. Navy. Daniels cited prewar naval preparations and strategy proposals made by other American leaders during the war to disprove Sims' charges.

Despite the public acrimony, Sims emerged with his reputation unharmed, although some historians believe it cost him promotion to the rank of Admiral of the Navy. He did however serve a second tour as president of the Naval War College (1919–1922).[4] It was during his time at the Naval War College that he wrote and published his book The Victory at Sea which describes his experiences in World War I. In 1921 The Victory at Sea won the Pulitzer Prize for History. Sims is, possibly, the only career naval officer to win a Pulitzer Prize. (Rear Admiral Samuel E. Morison won two Pulitzer Prizes but only served nine years in the Naval Reserve.)

Retirement and death

Sims retired from the Navy in October 1922, having reached the mandatory retirement age of 64. In retirement he lived at 73 Catherine Street in Newport, Rhode Island. He appeared on the cover of the October 26, 1925 issue of Time magazine and was the subject of a feature article. He was promoted to full admiral on the retired list in 1930.

Admiral Sims died in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1936 at the age of 77. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[5]

Personal life

Sims married Anne Erwin Hitchcock, who was sixteen years his junior, in 1905. The couple had five children, three daughters (Margaret, Adelaide and Anne) and two sons (William S. Sims, Jr. and Ethan Sims). Mrs. Sims died in 1960 at age 85.

Awards

His account of the U.S. naval effort during World War I, The Victory at Sea,[6] won the 1921 Pulitzer Prize for History. In 1929 was honored with a Doctor of Laws from Bates College.

Columbia University conferred the honorary degree of doctor of laws upon Rear Admiral Sims on 2 June 1920.[7] Several weeks later, Williams College conferred on him the honorary degree of doctor of laws during its June 21, 1920, commencement exercises.[8]

Four U.S. Navy vessels have been named for Sims. Two ships have been named USS Sims—the World War II-era destroyer USS Sims (DD-409) and destroyer escort USS Sims (DE-154). A transport vessel was named USS Admiral W. S. Sims. Additionally the Knox-class frigate USS W. S. Sims (FF-1059) was commissioned in 1970 and decommissioned in 1991.

The United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp panel on February 4, 2010. One of the stamps depicted Admiral Sims.[9]

In 1947, the Naval War College acquired an existing barracks building, which they converted to a secondary war-gaming facility, naming it Sims Hall after its former president.

Honours and awards

- United States military awards;

- Distinguished Service Medal (declined in a dispute with Secretary Daniels over awards)

- Spanish Campaign Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal

- Mexican Service Medal

- Victory Medal

- Foreign honors;

- Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (United Kingdom) (1918)

- Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour (France) (1919)

- Grand Cordon in the Order of Leopold (Belgium)[10]

- Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown of Italy

- Other honors;

- Theodore Roosevelt Association Distinguished Service Medal (1926)

- American Legion Distinguished Service Medal (1930)

- Pulitzer Prize for History (1921)

Dates of rank

- Cadet Midshipman, United States Naval Academy - 24 June 1876

- Midshipman - 22 June 1880

- Ensign (junior grade) - 3 March 1883

- Ensign - 26 June 1884

- Lieutenant (junior grade) - 9 May 1893

- Lieutenant - 1 January 1897

- Lieutenant Commander - 21 November 1902

- Commander - 1 July 1907

- Captain - 4 March 1911

- Rear Admiral - Selected on 29 August 1916, but remained number 31 of 30 flag officers remaining in the rank of captain while awaiting billet until 23 March 1917.

- Vice Admiral (temporary) - 25 May 1917

- Admiral (temporary) - 4 December 1918

- Rear Admiral - Upon returning to the Presidency of the Naval War College on 11 April 1919

- Rear Admiral, Retired List - 15 October 1922

- Admiral, Retired List - June 21, 1930

See also

Notes

- ^ William N. Still. Crisis at Sea: The United States Navy in European Waters in World War I.

- ^ Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Vol. V, p. 52.

- ^ Michael Simpson, "Admiral William S. Sims, U.S. Navy, and Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, Royal Navy: An Unlikely Friendship and Anglo-American Cooperation, 1917–1919", Naval War College Review, Spring 1988, Vol. 41 Issue 2, pp. 66–80. JSTOR 44636883.

- ^ Coletta, 1991.

- ^ "Burial detail: Sims, William S". ANC Explorer. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ^ Sims, William (1920). The Victory at Sea. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co. p. 352.

- ^ The Washington Post. June 2, 1920. "Columbia to Honor Five". p 6, column 3.

- ^ The Washington Post (Washington DC). Tuesday, 22 June 1920. "Williams Honors Pershing. Admiral Sims and Franklin K. Lane Also Given LL.D's." no. 16,079, p 6, column 6.

- ^ "Distinguished Sailors Saluted On Stamps". USPS release no. 10-009.

- ^ Rd of 22.12.1919

References

- Allard, Dean C., "Admiral William S. Sims and United States Naval Policy in World War I" in American Neptune 35 (April 1975): 97–110.

- Coletta, Paolo E. "Naval Lessons of the Great War: The William Sims-Josephus Daniels Controversy," American Neptune, Sept 1991, Vol. 51 Issue 4, pp 241–251

- Hagan, Kenneth J., "The Critic Within" in Naval History (December 1998): 20-25

- Hagan, Kenneth J., "William S. Sims: Naval Insurgent and Coalition Warrior" in The Human Tradition in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era Ballard C. Campbell, ed. (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 2000), 187-203

- Hagan, Kenneth J., and Michael T. McMaster, "His Remarks Reverberated from Berlin to Washington," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (December 2010): 66–71.

- Little, Branden, and Kenneth J. Hagan, "Radical, But Right: William Sowden Sims (1858–1936)" in Nineteen Gun Salute: Case Studies of Operational, Strategic, and Diplomatic Naval Leadership during the 20th and early 21st Centuries, eds. John B. Hattendorf and Bruce Elleman (Newport, RI and Washington, D.C.: Naval War College Press & Government Printing Office, 2010), 1-10.

- Morison, Elting E., Admiral Sims and the Modern American Navy (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1942), the standard scholarly biography, by the husband of his daughter Anne Hitchcock Sims

- Simpson, Michael, "William S. Sims, U.S. Navy, and Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, Royal Navy: An Unlikely Friendship, and Anglo-American Cooperation" in Naval War College Review, Vol. 41 (Spring 1988): 60-80

- Steele, Chuck. "America's Greatest Great-War Flag Officer," Naval History Magazine (2013) 27#3 online

External links

- Sims (DD-409), Dictionary of American Fighting Naval Ships Archived 2004-09-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Admiral W.S. Sims (AP-127) Dictionary of American Fighting Naval Ships

- Naval History Bibliography, World War I, 1917-198, Naval Historical Center

- Register of the Papers of William S. Sims

- History of the Naval War College (from NWC website) Archived 2004-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Works by William Sims at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Sims at the Internet Archive

- William S. Sims Navigation Notes, 1892 MS 373 held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy

- Admiral Jellicoe Greets Admiral Sims, 20:53 to 21:35, and the First American Destroyers Arrive in England, 21:36 to 24:10