Океанические языки

| Океанический | |

|---|---|

| Географическое распределение | Океания |

| Лингвистическая классификация | австронезийский |

| Протоязык | Протоокеанический |

| Подразделения | |

| Коды языков | |

| ИСО 639-3 | – |

| Глоттолог | ocea1241 |

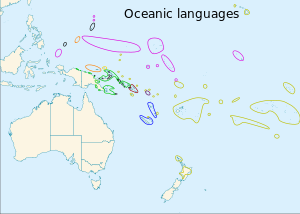

Ветви океанической (нижние четыре можно объединить в одну ветвь — Центрально-Восточная океаническая )Черные овалы на северо-западной границе Микронезии — это неокеанические малайско-полинезийские языки палау и чаморро . Черные круги внутри зеленых кругов — это офшорные папуасские языки . | |

Около 450 океанических языков являются ветвью австронезийских языков . Область, занимаемая носителями этих языков, включает Полинезию , а также большую часть Меланезии и Микронезии . Хотя океанические языки охватывают огромную территорию, на них говорят всего два миллиона человек. Крупнейшими отдельными океаническими языками являются восточнофиджийский с более чем 600 000 говорящих и самоанский с приблизительно 400 000 говорящих. Языки гильберта (кирибати), тонганский , таитянский , маори и толай ( полуостров Газель ) имеют более 100 000 говорящих каждый. Общий предок , который реконструируется для этой группы языков, называется протоокеаническим (сокр. «POc»).

Классификация

Океанические языки были впервые показаны как языковая семья Сиднеем Гербертом Рэем в 1896 году и, помимо малайско-полинезийских , они являются единственной установленной крупной ветвью австронезийских языков . Грамматически они находились под сильным влиянием папуасских языков северной Новой Гвинеи , но они сохраняют удивительно большое количество австронезийского словаря. [1]

Линч, Росс и Кроули (2002)

According to Lynch, Ross, & Crowley (2002), Oceanic languages often form linkages with each other. Linkages are formed when languages emerged historically from an earlier dialect continuum. The linguistic innovations shared by adjacent languages define a chain of intersecting subgroups (a linkage), for which no distinct proto-language can be reconstructed.[2]

Lynch, Ross, & Crowley (2002) propose three primary groups of Oceanic languages:

- Oceanic

- Admiralties linkage: languages of Manus Island, its offshore islands, and small islands to the west.

- Western Oceanic (WOc) linkage: languages of the north coast of Irian Jaya (Western New Guinea), Papua New Guinea (excluding the Admiralties) and the western Solomon Islands. West Oceanic is made up of three or four sub-linkages and families:

- ? Sarmi–Jayapura linkage: maybe part of the North New Guinea linkage?

- North New Guinea linkage: consists of languages of the north coast of New Guinea, east from Jayapura.

- Meso-Melanesian linkage: consists of languages of the Bismarck Archipelago and Solomon Islands.

- Papuan Tip linkage: consists of languages of the tip of the Papuan Peninsula.

- Central–Eastern Oceanic (CEOc) linkage: nearly all languages of Oceania not included in the Admiralties and Western Oceanic. Central–Eastern consists of four or five subgroups:

- Southeast Solomonic linkage: of the South East Solomon Islands.

- (Utupua–Vanikoro linkage: later removed to Temotu languages).

- Southern Oceanic linkage: consists of languages of New Caledonia and Vanuatu.

- Central Oceanic linkage: consists of the Polynesian languages, and the languages of Fiji.

- Micronesian linkage.

The "residues" (as they are called by Lynch, Ross, & Crowley), which do not fit into the three groups above, but are still classified as Oceanic are:

- St. Matthias Islands linkage.

- ? Yapese language: of the island of Yap. Perhaps part of the Admiralties?

Ross & Næss (2007) removed Utupua–Vanikoro, from Central–Eastern Oceanic, to a new primary branch of Oceanic:[3]

- Temotu linkage, named after the Temotu Province of the Solomon Islands.

Blench (2014)[4] considers Utupua and Vanikoro to be two separate branches that are both non-Austronesian.

Ross, Pawley, & Osmond (2016)

Ross, Pawley, & Osmond (2016) propose the following revised rake-like classification of Oceanic, with 9 primary branches.[5]: 10

- Oceanic

- Yapese language

- Admiralty languages

- St Matthias languages (Mussau and Tench)

- Western Oceanic linkage

- Meso-Melanesian linkage

- New Guinea Oceanic linkage

- Temotu languages

- Southeast Solomonic languages

- Southern Oceanic linkage

- North Vanuatu linkage

- Nuclear Southern Oceanic linkage

- Micronesian languages

- Central Pacific languages

- Western Central Pacific linkage

- Eastern Central Pacific linkage

Non-Austronesian languages

Roger Blench (2014)[4] argues that many languages conventionally classified as Oceanic are in fact non-Austronesian (or "Papuan", which is a geographic rather than genetic grouping), including Utupua and Vanikoro. Blench doubts that Utupua and Vanikoro are closely related, and thus should not be grouped together. Since each of the three Utupua and three Vanikoro languages are highly distinct from each other, Blench doubts that these languages had diversified on the islands of Utupua and Vanikoro, but had rather migrated to the islands from elsewhere. According to him, historically this was due to the Lapita demographic expansion consisting of both Austronesian and non-Austronesian settlers migrating from the Lapita homeland in the Bismarck Archipelago to various islands further to the east.

Other languages traditionally classified as Oceanic that Blench (2014) suspects are in fact non-Austronesian include the Kaulong language of West New Britain, which has a Proto-Malayo-Polynesian vocabulary retention rate of only 5%, and languages of the Loyalty Islands that are spoken just to the north of New Caledonia.

Blench (2014) proposes that languages classified as:

- Austronesian, but perhaps actually non-Austronesian are spoken in northern Vanuatu and southern Vanuatu (North Vanuatu languages and South Vanuatu languages).

- Austronesian, but may have experienced bilingualism with non-Austronesian are spoken in central Vanuatu and New Caledonia (Central Vanuatu languages and New Caledonian languages).

- non-Austronesian, with some other languages traditionally classified as Austronesian may perhaps actually be non-Austronesian are spoken in the Solomon Islands and New Britain (various Meso-Melanesian languages).

Word order

Word order in Oceanic languages is highly diverse, and is distributed in the following geographic regions (Lynch, Ross, & Crowley 2002:49).

- Subject–verb–object: Admiralty Islands, most of Markham Valley, Siasi Islands, most of New Britain, New Ireland, some parts of Bougainville Island, most parts of the southeast Solomon Islands, most parts of Vanuatu, some parts of New Caledonia, most of Micronesia

- Subject–object–verb: central and southeast Papua New Guinea, some parts of Markham Valley, Madang coast, Wewak coast, Sarmi coast, a few parts of Bougainville, some parts of New Britain

- Verb–subject–object: New Georgia, some parts of Santa Ysabel Island, much of Polynesia, Yap

- Verb–object–subject: Fijian language, Anejom language, Loyalty Islands, Kiribati, many parts of New Caledonia, Nggela

- Object-initial: only two, Äiwoo (object-verb-subject) and Tobati (object-subject-verb)

- Topic-prominent language: much of Bougainville Island, Choiseul Island, some parts of Santa Ysabel Island

See also

References

- ^ Mark Donohue and Tim Denham, 2010. Farming and Language in Island Southeast Asia: Reframing Austronesian History. Current Anthropology, 51(2):223–256.

- ^ The Wave model is more appropriate than the Tree model for representing such linkages: see François, Alexandre (2014), "Trees, Waves and Linkages: Models of Language Diversification" (PDF), in Bowern, Claire; Evans, Bethwyn (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics, London: Routledge, pp. 161–189, ISBN 978-0-41552-789-7.

- ^ Ross, Malcolm and Åshild Næss (2007). "An Oceanic Origin for Äiwoo, the Language of the Reef Islands?". Oceanic Linguistics. 46 (2): 456–498. doi:10.1353/ol.2008.0003. hdl:1885/20053.

- ^ a b Blench, Roger. 2014. Lapita Canoes and Their Multi-Ethnic Crews: Might Marginal Austronesian Languages Be Non-Austronesian? Paper presented at the Workshop on the Languages of Papua 3. 20–24 January 2014, Manokwari, West Papua, Indonesia.

- ^ Ross, Malcolm; Pawley, Andrew; Osmond, Meredith (eds). The lexicon of Proto Oceanic: The culture and environment of ancestral Oceanic society. Volume 5: People: body and mind. 2016. Asia-Pacific Linguistics (A-PL) 28.

Bibliography

- Ray, Sidney H. (1896). "The common origin of the Oceanic languages". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 5 (1): 58–68. JSTOR 20701407.

- Lynch, John; Ross, Malcolm; Crowley, Terry (2002). The Oceanic Languages. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1128-4. OCLC 48929366.

- Ross, Malcolm and Åshild Næss (2007). "An Oceanic Origin for Äiwoo, the Language of the Reef Islands?". Oceanic Linguistics. 46 (2): 456–498. doi:10.1353/ol.2008.0003. hdl:1885/20053.